Widowed Amy, Countess of Blakemore, is utterly focused on the arrangements for her daughter’s wedding. She needs no distractions, or surely it won’t all get done on time! Then, for the first time, she meets her son-in-law-to-be’s much older half-brother, who proves to be more distracting then she could ever have imagined. William Easton, Baron Hartley, had shown no interest in marrying again, since the mother of his two daughters died. Now, as his half-brother is about to marry, the idea suddenly seems much more appealing. Of course, that might just be because he can’t take his eyes off the beautiful mother of the bride-to-be. But will she accept his suit?

|

My latest novella "Mother of the Bride" is found in Regency Summer Weddings, an anthology published by Dreamstone Publishing. Additional stories from other award-wining, best-selling authors Arietta Richmond, Regina Jeffers, Olivia Marwood, and Janis Susan May. Available in Amazon Kindle and free for members of Kindle Unlimited. Mother of the Bride by Victoria Hinshaw Widowed Amy, Countess of Blakemore, is utterly focused on the arrangements for her daughter’s wedding. She needs no distractions, or surely it won’t all get done on time! Then, for the first time, she meets her son-in-law-to-be’s much older half-brother, who proves to be more distracting then she could ever have imagined. William Easton, Baron Hartley, had shown no interest in marrying again, since the mother of his two daughters died. Now, as his half-brother is about to marry, the idea suddenly seems much more appealing. Of course, that might just be because he can’t take his eyes off the beautiful mother of the bride-to-be. But will she accept his suit? My interior cover picture is a detail from the English Carriage Costume in LaBelle Assemblee Magazine, February 1818: Round dress of fine cambric muslin, superbly embroidered round the border in three distinct rows. Pelisse of rich Tobine silk striped, of Christmas holly-berry color, and bright grass green, trimmed round collar, cuffs and down the front with very broad swansdown.

0 Comments

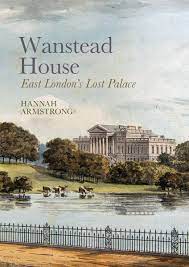

Not unexpectedly, I fell into another research rabbit hole while working on a novella, "Mother of the Bride," included in the regency summer collection from Dreamstone Publishing this year, Regency Summer Weddings. Now Available: At Amazon Recently I wrote in this blog about Palladian Bridges and included a bit about Palladian architecture in general. In this regard, I read about the now-demolished Wanstead House, pictured above. And the terrible scandals tied to the marriage of heiress Catherine Tynley Long, known as the Wiltshire Angel, and William Wellesley Pole, a nephew of the 1st Duke of Wellington. Below left, Catherine (1789-1825) and William (1788-1857 ). Above, The Angel and the Cad: Love, Loss and Scandal in Regency England is an excellent account of both the 1812 marriage and the mansion's fate by author Geraldine Roberts, published in 2015. Another excellent source is the website Wicked William, from Greg Roberts. From Wikipedia: "Wanstead House was a mansion built to replace the earlier Wanstead Hall. It was commissioned in 1715, completed in 1722 and demolished in 1825. Its gardens now form the municipal Wanstead Park in the London borough of Redbridge." Below, many bits and pieces from the estate can still be found. Left is a pillar from the gate; right, the grotto. Photo from British Listed Buildings. Above left, another source for learning about Wanstead is Wanstead House: East London's Lost Palace by Hannah Armstrong, published in 2022, covering the history, architecture, sale of contents and demolition in 1824-25. Right, a drawing of the original plan by Scottish Architect Colen Campbell (1676-1729). The Wanstead design shortly preceded the design of Burlington House, London, for Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Burlington, an early proponent of the neo-Palladian style. William Kent (1685-1748) was in charge of the interiors of both residences. below, a Hogarth painting of the interior, The Assembly at Wanstead House, 1728-32, now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Above, a brighter painting by Flemish painter Joseph Francis Nollekens of the Family of Sir John Tylney in the saloon of Wanstead House, 1740, Fairfax House, York Civic Trust. It was the décor above that William decided to update after he gained control of Catherine's fortune, just one of his myriad extravagances, including gambling and adultery, which left the couple penniless and needing to flee Britain with their children by 1823. Heartbroken and suffering from illness, perhaps a venereal disease her husband gave her, Catherine was successful in getting her children and herself back to England, where she made certain her children were protected from William before she died in 1825. No surprise to Regency aficionados, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, William's uncle, guaranteed the control of the children remained with Catherine's sisters, Dora and Emma, though none ever fully recovered from their abusive father's influence. Below left, drawing of the Gardens "in their heyday" from the London Gardens Trust; right, Pastoral scene before Wanstead House and Basin, by William Havell, 1815, Yale Center for British Art. All this research refreshed my knowledge of the situation, which will contribute to no more than a line or two of conversation in my novella. Of course, I enjoyed every moment of the effort. That's half the fun of writing regencies. Nevertheless, the excessively abusive behavior of Catherine's husband, who eventually was named 4th Earl of Mornington and did not die until 1857, more than thirty years after his unfortunate wife Catherine, stings even today. Certainly the epitome of a cad!

For a happier story, look for the Anthology titled Regency Summer Weddings, in the summer of 2024. My story is "Mother of the Bride." Montacute House is an Elizabethan-era house in Somerset which I visited in July 2018 while on my way from Lyme Regis to Bath with the JASNA tour. The West Front, above, was added to the house in 1787. The East Front, below, opens into the courtyard, now a garden and lawn. The house was built in the late Elizabethan period, about 1598, a typical Prodigy House of the era. The owner was Sir Edward Phelips (c.1555-1614), a wealthy lawyer and politician, Speaker of the House of Commons, one of the prosecutors of the 1605 Gunpowder Plotters, and later named Master of the Rolls. The East Front exhibits an English Renaissance style, in the words of the website, the house "...must have seemed beyond the dreams of most of those who lived nearby, a work of astonishing splendour and pride...The architecture is a mix of two styles, the traditional Gothic and the new fashionable Renaissance...built on a grand scale with turrets, obelisks, shell niches, pavilions and walls of glass. On the east front stand the Nine Worthies, statues of biblical, classical and medieval figures, including Julius Caesar and King Arthur." The Phelips family descendants lived at Montacute for more than 300 years before leasing it out in the early 20th century. Among the residents was Lord Curzon after his term as Viceroy of India. Once his wife died, he came to live at Montecute around 1915, sometimes with his mistress, the novelist Elinor Glyn. Lord Curzon installed modern plumbing, but only in his own bedroom. The original plan of the house followed the medieval pattern of a Great Hall connected to subsequent more private chambers, without corridors. The remodeling of the house in the 18th century added a central corridor and the arrangement of rooms was altered. Above, entrance into the Great Hall. Above and below, views of the Great Hall. Below, the Drawing Room. The portrait of three men hunting over the fireplace is by Daniel Gardner (1750-18050. This drawing room was once a bedchamber; it is now furnished in the 18th century style. The red upholstered mahogany chairs are by William Linnell (1703-1763) of London, and were commissioned by Sir Richard Hoare for the drawing room at Barn Elms in 1753. Above, the cabinet on a stand, left, is English, in the Japanese style, in lacquer and gilt, dating from the mid-18th century. The console table, at right, with the gilded eagle and marble top, dates from the mid-19th century. The Library at Montacute House, Somerset ©National Trust Images/James Dobson. Most of the pictures were taken by me, but I failed to get a good overall shot of the former Great Chamber, now the library. Below, a corner detail, and the great fireplace. Below, the Great Chamber/Library window with the arms of the family. Montacute played the role of Cleveland House, the country home of Mr. and Mrs. Palmer in the 1995 film of Sense & Sensibility. Garden views. The gardens with their quaint corner pavilions are lovely. Once probably used as small banqueting halls, the pavilions are empty now. The Orangery. The Montacute Phelips Lions. Next, the Long Gallery and an exhibition of portraits related to Queen Elizabeth II's ancestors, focusing on Elizabeth of Bohemia, 'The Winter Queen.'

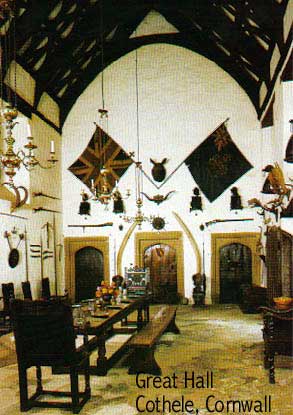

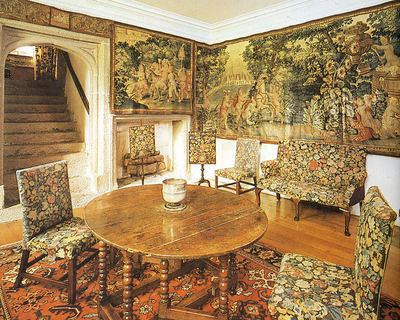

Another recycled post from November, 2018, with a few revisions, which I hope you will enjoy. Haddon Hall near Bakewell in Derbyshire is a fine example of a medieval house which grew into a Tudor estate and has been "virtually unchanged" since the 17th century. Unlike so many country houses, which are remodeled with almost each generation, Haddon has retained it essential early features. Haddon Hall became the property of the Manners family, Dukes of Rutland, by the marriage of Dorothy Vernon (daughter of Sir George Vernon ) to John Manners in 1563. The Manner family home is Belvoir Castle, and like many families with several estates, they tended to stay there, leaving Haddon uninhabited for the most part This was a common pattern, leaving a wife's estate in limbo while entering family activities at the husband's properties. The unintended consequence is the fine condition of some early homes which were inherited by women. Above, my pictures from a recent visit, showing the fine restoration of the rooms carried on by Lord Edward Manners (born 1965), brother of the current 11th Duke of Rutland (born 1959). Cothele sits on the Tamar River, the boundary between Devon and Cornwall. Like Haddon, it is a medieval-cum-Tudor house which retains its early features. The property came into the Edgecumbe family -- who owned it until after World War II -- when Richard Edgecumbe married the heiress Hilaria de Cothele in 1353. The National Trust took over in 1947. Beautiful gardens are terraced down the hillside, essentially a Victorian creation.  Wisteria seems to enhance every building it accompanies. Perhaps it is at its loveliest upon gray stone walls and lead-paned windows. No one has noted the age of this example, but one can assume it is very, very old. The Great Hall at Cothele is similar to the Great Halls in all ancient country houses, the area where the community dined together, played, worked, even slept in the earliest houses. Traditionally the three doors in the screen wall led to the kitchen, the buttery, and the pantry. Among the most admired and unique features of Cothele is the collection of tapestries from the 16th and 17th centuries. Observers have attributed the fine condition o the hangings to "benign neglect" since the family maintained the house while living elsewhere most of the time. Like so many ancient estates, Cothele was an agricultural community and home to dozens of families who occupied the tenant farms and businesses such as the mill (above right) and the shipping center on the river (left).

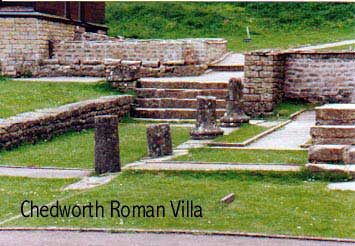

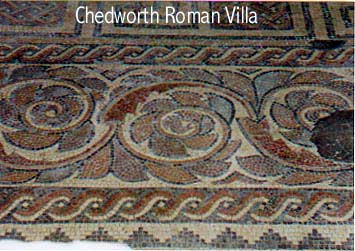

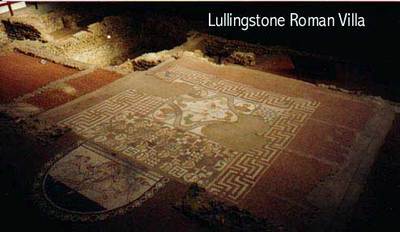

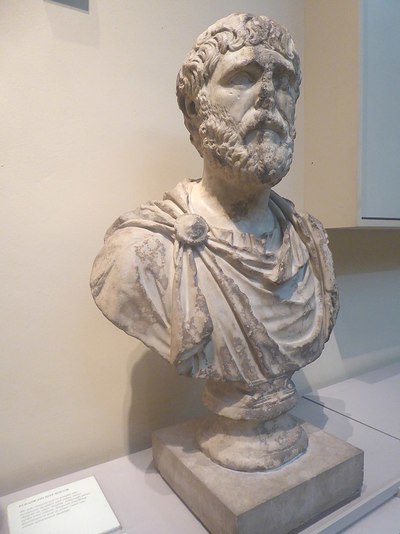

My take, repeated from from 2018, on the Romans' contributions to the tradition of English Country Estates. Though we often forget such ancient history in regard to Country Houses in Britain, the first ones we know of were actually from the period of Roman control beginning with the conquest in 43AD. The first Roman villa I visited was Chedworth, above, a National Trust property since the 1920's. The Romans built in stone so like the wisest of The Three Pigs, their structures lasted for centuries, however knocked down, covered over or otherwise demolished they were. And they embellished their buildings with mosaics like these.   Above is an artist's rendition of the Chedworth villa in the fourth century from the Wikipedia site. In addition to a luxurious dwelling, it contained farm buildings, and their associated activities. Located in the Cotswold Hills in Gloucestershire, they probably raised sheep, a cash industry in Britain since time immemorial. Below, mosaics from the Bignor Roman Villa in West Sussex, another well developed site for studying the Romano-British culture which stretched over four centuries, a very long time. Medusa, above, and a Dolphin, below. The Bignor Roman villa has impressive mosaics and some reconstructions of what Roman houses may have looked like nearly two thousand years ago. The Fishbourne Roman Palace, also in West Sussex, is the largest Roman residence yet discovered in Britain, as well as being among the earliest; it dates from about 75 AD. It has been extensively examined, and shows all the attributes the Romans developed to create central heating, running water and other conveniences forgotten for centuries thereafter. Many other Roman sites can be visited throughout Britain. In addition to the villas, many Roman artifacts--statues, tools, jewelry and others--are in museums across the country. There are Roman remains from the Channel coast north to Hadrian's Wall and its associated forts, erected across Britain east-west to protect from invasion by the fierce Scots. I just can't leave this topic without a mention of a few of my other favorite Roman remnants in Britain. For example, below, fragments of the Roman Wall in London. Photo above: By John Winfield, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3186845 Below, the Roman-style columns of the British Museum, a treasure trove of Roman artifacts -- among a few other cultures!! Below, a Mithraic altar, coins, and a wonderful book, all from the British Museum. Click on the photos for larger versions. Last year, I visited the remains of the Roman Amphitheater discovered during the rebuilding of the Guildhall Art Museum in the City of London. And perhaps the most famous of the Roman remains, the bathing facilities in Bath. Bath's Aqua Sulis was a tourist center many centuries ago, as it is today. Above, Sulis Minerva, the goddess who united the Celtic goddess Sulis with the Roman deity Minerva, representing the healing powers of the hot springs. I am here to endorse those healing powers -- I definitely felt better after trying out the Thermae Bath pools in modern-day Bath, A true delight! Those Romans were very clever to take the local springs and use them so wisely!

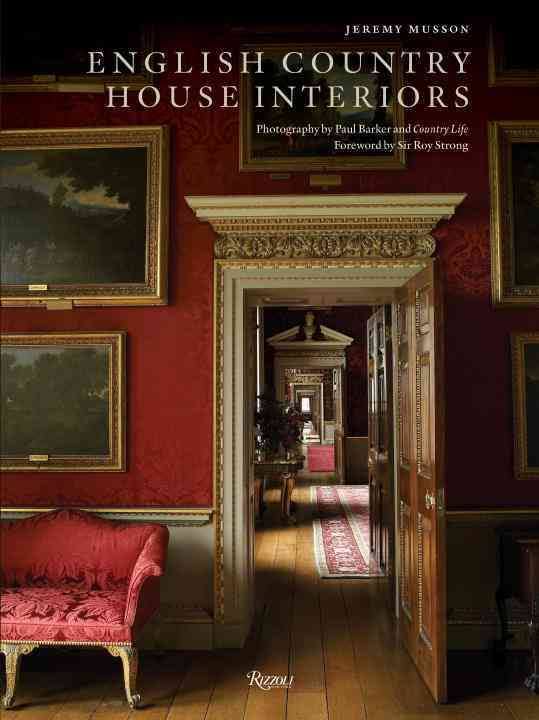

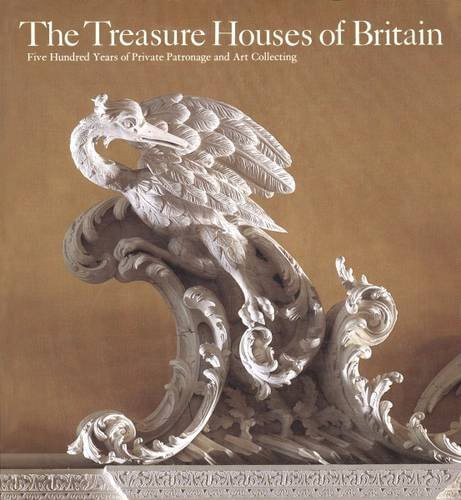

This post originally ran in November, 2018. I am re-posting it and several more as newly relevant to some upcoming subjects. Enjoy!!!  I recently attended a lecture by Jeremy Musson, whose many books are a constant source of delight, if a bit too heavy to carry around. However, I toted one home anyway. I photographed Mr. Musson in 2012 at the Milwaukee Art Museum where I listened to him talk about one of his previous books (which I also bought of course) English Country House Interiors. Mr. Musson wrote for many years for Country Life magazine and visited a large percentage of the country houses in Britain. In his new volume he partners with David Cannadine in their volume for Rizzoli and the Royal Oak Society, American affiliate of Britain's National Trust. Mr. Cannadine's essay opening the volume explains the significance of the 1985-86 exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C. As a serendipitous coincidence, we toured this exhibition, and its catalogue has long been one of my prize possessions. I have gone on in the subsequent decades to study and visit as many Stately Homes as I can, not only in Britain but also in the U.S. and on my travels elsewhere. The photo above, from the National Gallery's website, shows part of the installation of the exhibition featuring the marble statue Three Graces by Canova, which was purchased in 1994 from its then-owner the Duke of Bedford of Woburn Abbey. It has since been shared by its newer owners, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London and the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. As I page through the Treasure Houses catalogue, I am surprised and gratified at how many of the objects--paintings, sculpture, furniture, china, etc.--I have visited in situ since my first forays into the splendors of the country houses and their collections. Above is the magnificent sofa, c 1762-65, from Kedleston Hall's Drawing Room designed by Robert Adam and executed by the firm of John Linnell. Also by Linnell for an Adam-designed house are these chairs from Osterley Park. Getting back to the The Country House, Past Present and Future, the cover picture shows us Uppark in West Sussex, a house which the National Trust painstakingly restored after a terrible fire in 1989. Below, the fire on August 30, 1989. Fortunately, most of the furnishings, paintings and decorative arts on the ground floor were saved by brave volunteers, but the roof was destroyed and collapsed. The 17th century house not only had a heritage of fine collections and architectural significance, but it also had a fascinating history of inhabitants before it was turned over to the NT in 1954. The Trust decided to restore the house after the fire and it was re-opened in 1995 after years of careful restoration. Fire struck again in 2015 when Clandon House, an 18th century architectural gem burned. Again, many of the furnishings were saved and the NT has begun restorations. The picture on the right shows the house as it was when we visited a few years before the fire.  Before I wander off topic a bit again, as I do so often, come with me briefly to Sudbury Hall in Derbyshire. The first time I visited, shortly after the 1995 TV version of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice was shown in the U.S., the version with Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle, the House was exhibiting a selection of the costumes from the film.  After looking at the costumes, we enjoyed all the attraction of the lovely old house, assisted by the usually voluble and patient volunteers for the NT. However, when we reached the Red Room, a handsome bedchamber, we ran into a curmudgeon. "Ooh," we exclaimed. "This is the room where Mr Darcy changed his coat!" The volunteer guide was downright offended. "Madam!" he huffed. "This was the bedroom of Queen Adelaide!" We apologized and heard this story. After the death of King William IV in 1837, his widowed queen spent several years traveling among country houses away from the Court. Though Queen Victoria was sincerely fond of her aunt Adelaide, apparently the Duchess of Kent resented her influence. So she politely stayed away. This little story illustrates two points. First, even when run by the National Trust, they can use the income from films and TV, no matter if it annoys their volunteers. Secondly, the families and individuals associated with these houses are often more interesting then the estates themselves. In the volume ostensibly the subject of this blog, Jeremy Musson and his essayists discuss many topics associated with the study and enjoyment of country houses. not the least of them the 'Downton Effect.' As he notes, the country house 'business' has never been better. Building on books and films such as Brideshead Revisited, the Jane Austen phenomenon, and so forth, we are all captivated by the stories, whether real or fictional, of life in stately homes, whether above or below stairs. For further captivation, I highly recommend a comfy chair, a cup of tea, and an afternoon (or several) devoted to reading and gazing at The Country House, Past, Present and Future.

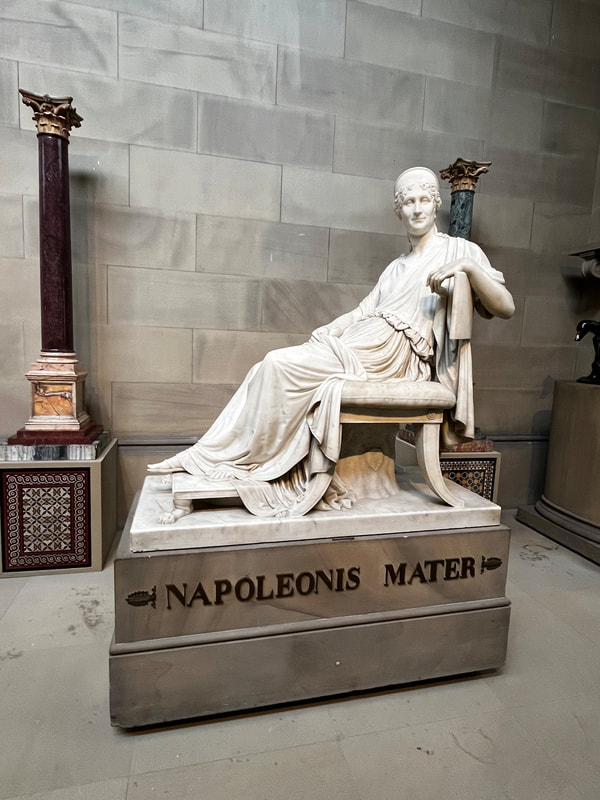

Antonio Canova (1757–1822) Wiki: "was an Italian Neoclassical sculptor, famous for his marble sculptures. Often regarded as the greatest of the Neoclassical artists, his sculpture was inspired by the Baroque and the classical revival, and has been characterised as having avoided the melodramatics of the former, and the cold artificiality of the latter." Well said.  Above, Self Portrait, Antonio Canova, 1792. Below, Venus Victrix, by Canova, 1805-08, Borghese Gallery, Rome, 2023. Pauline Bonaparte Borghese, (1780-1825) posed for this sculpture, though accounts vary on whether she was semi-nude or not. Wikipedia and other sources report the possibility that she quipped the studio had a stove and was warm. Please click for larger pictures. Above left, a side view. Right, a plaster cast in the Museum in Possagno; the gentleman behind her head is about to tell me that no photos are allowed, though I had already taken this one and another (below). Below, the Museo Canova in Possagno, actually his tomb; right, a plaster cast of Canova's sculpture Napoleon as Mars, the Peacemaker, aka Mars the God of War. (You choose.). Above left, a model of the original; this copy stands in the Palazzo Bonaparte in the Piazza Venezia in Rome, one of the homes of Napoleon's mother, Letizia, also known as Madame Mere. We visited both to see the building and a vanGogh exhibition on our Rome trip in 2023. Below, Mars, the original statue Canova made for Napoleon. However, the Emperor did not like it and it sat in the basement of the Louvre until after his defeat at Waterloo. The Prince Regent eventually purchased and presented it to the victorious Duke of Wellington. It stands today in the staircase at Apsley House, the Wellington Museum in London. The floors beneath it had to be reinforced to bear the weight of the ten-foot tall statue. Above left, a Canova sculpture of Napoleon's mother in the Chatsworth Gallery. Right, Endymion. from Wikipedia: In May 1819, the 6th Duke of Devonshire, on his first trip to Rome, paid a visit to the studio of the most celebrated sculptor of the time, Antonio Canova. He marvelled at what he saw and commissioned a marble statue from Canova, leaving both its size and subject to the sculptor to decide, and paying a deposit in advance. The marble was roughed out by 1822, when Canova asked for a further £1,500. It was completed before his death later that year. It arrived in London the following year and caused a stir when first displayed at Devonshire House in Piccadilly.... In Greek mythology, Endymion was a handsome shepherd boy of Asia Minor, the earthly lover of the moon goddess Selene, and each night he was kissed to sleep by her. She begged the god Zeus to grant him eternal life so she might be able to embrace him forever. Zeus granted her wish and put Endymion into eternal sleep. The highly polished finish on Canova's statue is believed to represent the reflected light of the moon goddess. Below left, another view of Endymion; right, a closer view of his companion canine. Above left, The Three Graces in The Hermitage, St. Petersburg. By Canova, the marble sculpture portrays the mythological three Charities, daughters of Zeus, who represent youth/beauty (Thalia), mirth (Euphrosyne), and elegance (Aglaea). Right, a second version of the Three Graces is owned jointly and exhibited in turn by the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Scottish National Gallery. John Russell, the 6th Duke of Bedford, visited Canova's studio in Rome in 1814 and had been immensely impressed by a carving of the Graces which Canova produced for the Empress Josephine. When the Empress died in May of the same year, he offered to purchase the completed piece, now in Russia. Undeterred, the Duke commissioned another version for himself. In 1819 it was installed at the Duke's residence in Woburn Abbey. This item is now owned jointly, as indicated above. Below, left, The Three Graces, in the V&A. Right, a version of three males, in the V&A's exhibition, Fashioning Masculinity in 2022. Above left, Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss, Louvre; right, detail.

I could write on for ages on Canova's brilliant output, his international fame, the urgent pleas made to him for original work, or if necessary, copies. But I will close this blog with a sculpture exhibited in three of the world's most prestigious museums, the Louvre in Paris, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, and the Metropolitan in New York City. Wikipedia covers it perfectly: "Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss was commissioned in 1787 by Colonel John Campbell. It is regarded as a masterpiece of Neoclassical sculpture, but shows the mythological lovers at a moment of great emotion... the god Cupid in the height of love and tenderness, immediately after awakening the lifeless Psyche with a kiss... Joachim Murat acquired the first or prime version in 1800. After his death the statue entered the Louvre Museum in Paris, France in 1824; Prince Yusupov, a Russian nobleman acquired the 2nd version of the piece from Canova in Rome in 1796, and it later entered the Hermitage... A full-scale model for the 2nd version is in the Met. Below, the Met's version, a copy in plaster. The number of sculptures I admire is endless. Here are a few more from Rome. Above, The Capitoline Venus from Wikipedia Commons against a dark background. This is another of the great ancient sculptures often seen in reproduction in museums, stately homes and garden settings, one of many representations of the goddess Venus or Aphrodite, the ideal of beauty and love. Capitoline Venus as it is displayed in the Capitoline Museum, Rome, in my photos from April, 2023. Content of the text label accompanying the statue: "The Capitoline Venus: The small octagonal room was built in the early 19th century to provide an evocative setting for one of the museum’s most famous sculptures. The statue, slightly larger than life size, was found sometime between 1667 and 1670 near the basilica of San Vitale and given to the Capitoline Museums by Pope Benedict XIV in 1752. The Goddess is nude, portrayed in a sensual but modest gesture, her arms attempting to hide the harmonious shapes of her body from the viewer’s sight. The objects at her feet, her nudity, and the arrangement of her hair indicate that she she is bathing. The statue is a variant of the Aphrodite sculpted by Praxiteles in the fourth century B.C. for the goddess’s shrine at Cnidus Turley The number of know replicas and variants of this work attest to its success in the Roman world. The high value ascribed to this statue is borne out by the fact that it was discovered hidden in a walled up space, where its owner hoped to save it from some impending danger." The statue is in Palazzo Nuovo on the Campidoglio. The Capitoline Venus was removed by Napoleon to Louvre and returned in 1816. About 50 copies exist, most in museums; more are found as garden sculptures. Below, the Capitoline Museum Buildings on the piazza as designed by Michelangelo. Please click on the images for larger versions. Above, bronze Equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor, created in 1981, a replica of the original which now resides indoors for its protection from the elements. Below, the original. Almost fourteen feet tall, the bronze was created about 175 AD and is one of few surviving bronzes from that period. It was originally elsewhere and moved to the Campidoglio as part of Michelangelo's design about 1538. Above, left, Lupa, the famous Roman sculpture of Romulus and Remus, the twins who founded the city, after being orphaned and raised by a she-wolf. Right, Boy with Thorn, aka Spinario, a bronze version; the same figure in marble can be found in the Uffizzi. Dated c.1st Century AD.

More sculptures to come. Have you a favorite? The Palladian Bridge, in the midst of the Stowe Landscape Garden, is an iconic symbol of the 18th C. English countryside. For many years, I yearned to visit, and at last, in May 2023, I achieved my wish, my fourth Palladian Bridge. Someplace, probably Wikipedia, I read that four Palladian Bridges existed in the world. Below, left, the first was built in 1736-37 at Wilton House in Wiltshire on the edge of Salisbury. Below, right, second was built the next year, 1738, at Stowe in Buckinghamshire. Please be sure to click on the small photos for complete versions. Above left, Prior Park, Bath, a copy of the bridge at Wilton house, was built in 1742 for Ralph Allen. Above right, the bridge at Stourhead in Wiltshire was designed by Henry Hoare II, finished in 1762, without a colonnade or pedimented arch. Now I have seen and/or walked across each of them. Below, left, a Marble bridge from Russia. When we visited St. Petersburg years ago, we toured the Catherine Palace in the countryside, but when I asked the guide if we could see the Palladian Bridge in the gardens, she laughed, explaining that it was far away and inaccessible to us. So I have to content myself by knowing I was in the neighborhood and looking at pictures from the web such as the one below, the Russian Marble Bridge as it appears on Wikipedia. One might, I suspect, say there are five Palladian Bridges in the world. Referring to the the image above, Wikipedia writes, "The Siberian Marble Gallery is a decorative pedestrian roofed Palladian bridge (gallery walkway) in Empress Catherine Park in the former royal residence Tsarskoye Selo (now town of Pushkin). ...It connects the Swan Islands — an artificial archipelago of seven islets in the landscape park of Tsarskoe Selo — spanning a rivulet flowing between several ponds. The bridge was modelled after the Palladian Bridge (1736) in the park of Wilton House, in England, and served as a showcase for Ural marble ... assembled in the workshop of Vincenzo Tortori in 1774...called Siberian due to its construction with marble from the Urals." Below left, the river at Wilton House, Wiltshire; right, looking through the columns at the park. Above left, approaching the bridge at Wilton; right, Rex Whistler's 1935 painting of Wilton House with the bridge at the left. Below, left, the Palladian Bridge at Stowe Gardens from a distance. The Stowe version is wider and without step stairs to allow carriages touring the grounds to pass through the bridge. Above, two views of the South Facade of the Palladian House at Stowe, built beginning in the late 17th century and continuing for the next. Some of Britain most famous architects, such as William Kent and Robert Adam, contributed to the final product. 'Palladian' is an architectural term for the style most popular in the new classical era of the 18th century based on the designs of Andrea Palladio (1508-80) in Venice and the Veneto region. Below, left, Palladio's Church of Giorgio San Maggiore in Venice; right, Villa Barbaro, in Treviso, Veneto, both by Palladio. The Royal Institute of Architecture (RIBA) website writes, "This is a Classical style, named after the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) whose work and ideas had a profound influence on European architecture from the early 17th century to the present day. Palladio re-interpreted Roman architecture for contemporary use ... In the United States, Palladianism remained the prevailing style for public buildings until the 1930s and has never quite gone out of fashion for domestic architecture. Even today, some contemporary architects are influenced by Palladio’s ideas on planning and proportion, without the use of elements of classical architecture." Below two examples of Palladian style in England. Left, the Mansion House, London, official residence of the Mayor of London, built by George Dance in the 1740's. Right, South facade of Stowe House, Buckinghamshire, designed and re-designed by numerous architects, but now appearing primarily as created by Robert Adam (1728-92). Above left, the White House, north and south facades; right, the Supreme Court, both in Washington D.C. My photo of Stowe House, others from Wikipedia Commons. Based on ancient Greek and Roman sources, the principle features of Palladian architecture are symmetry, proportion, balance, and grandeur-- with columns, colonnades, arches, pediments, porticos, and other classical elements. All reflected the sober values of republicanism epitomized in ancient Rome. Below left, La Rotonda, Vincenza, begun by Andrea Palladio in 1567; right, Chiswick House, 1729, designed by Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington (1694-1753), near London, built after Burlington's study of Italian architecture with his mentor William Kent (1685-1748). Above left, Thomas Jefferson began remodeling Monticello, Charlottesville, VA, in the late 17th C and continued work on the house and grounds until his death; right, Jefferson National Memorial, Washington, DC, designed by John Russell Pope, built in 1939-43. Below, Canaletto's painting Capriccio with Design for Palladio's Rialto Bridge is dated 1742. Text in the Royal Collection Trust says, "Palladio published his design for the Rialto Bridge in 1570 with the words: 'Most beautiful in my judgement is the design of the bridge which follows, and very well suited to the site … in the middle of a city, … one of the greatest and most noble in Italy … there is an enormous amount of trade … and the bridge came to be exactly … where the merchants gathered to do business.'" This design was not chosen but lives on in the Palladian Bridges now existing. Finally, below, my photographs of the Pulteney Bridge in Bath, not precisely a Palladian Bridge, but a commercial one in the style of the Rialto plan. It was designed by Robert Adam in the neoclassical style and constructed 1769-1775. Wikipedia says it cost £11,000. Like the Rialto and Firenze's Ponte Vecchio, 'Good shopping!'

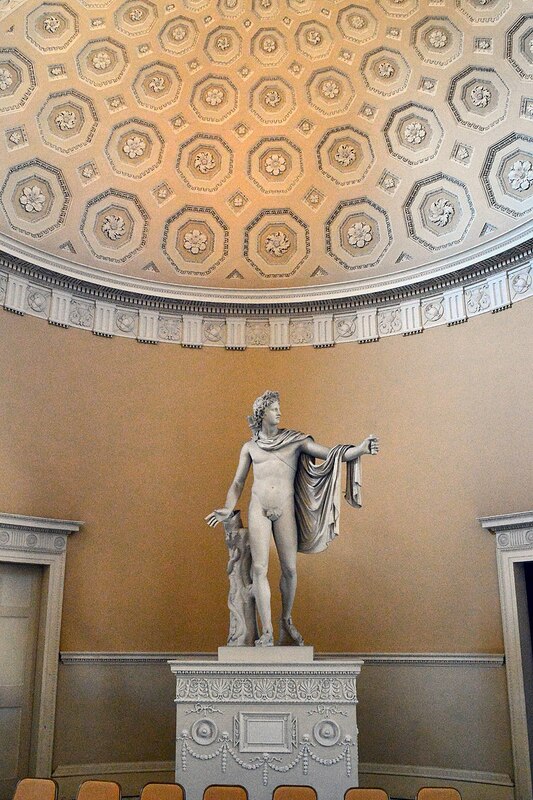

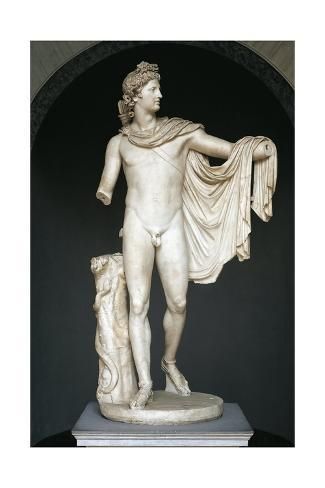

The Apollo Belvedere is an iconic sculpture, this copy in the garden at Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, England. Wikipedia writes, "a celebrated marble sculpture from classical antiquity...The work has been dated to mid-way through the 2nd century A.D. and is considered to be a Roman copy of an original bronze statue created between 330 and 320 B.C. by the Greek sculptor Leochares...rediscovered in central Italy in the late 15th century...placed on semi-public display in the Vatican Palace in 1511, where it remains...The lower part of the right arm and the left hand were missing when discovered and were restored by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (1507–1563), a sculptor and pupil of Michelangelo...From the mid-18th century it was considered the greatest ancient sculpture by ardent neoclassicists, and for centuries it epitomized the ideals of aesthetic perfection for Europeans and westernized parts of the world. In the words of the Vatican Museum's website: "This statue was part of the collection which Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere held in his palace in Rome. When he was elected Pope as Julius II (1503-1513) the statue was transferred to the Vatican...The god, Apollo, moves forward majestically and seems to have just released an arrow from the bow which he originally carried in his left hand." In 2022, London's Victoria & Albert Museum mounted an exhibit on men's fashions, above. It began, suitably, with "Undressed" using the Apollo Belvedere's unclothed body as its starting point. Below, copies of the famous statue as seen in numerous museums, country houses, and gardens. In the Neoclassical Age, no forms of art were more revered than those of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Below, Apollo in the Marble Hall of Kedleston Manor, as designed by the famed architect Robert Adam (1728-92). Above left and right, at Kedleston in Derbyshire. Below, at the opposite end of the Great Hall from The Dying Gaul at Syon House in Greater London. Below left, in bronze, at Huntington Museum and Gardens, in California. Right, the Apollo on the insgnia of NASA's Apollo 17, the sixth moon landing, in 1972 . Below, as originally discovered in the late 15th Century at Porto Anzio in Italy. Below, an etching of Sir Thomas Lawrence's Private Sitting Room in December, 1830, after the painter's death, published by Archibald Keightley, executor of the estate. In the back row of reproductions, we find our Apollo on the far left, National Portrait Gallery. One cannot imagine how many of versions of the Apollo Belvedere exist in marble, bronze, and plaster. I suspect it can be be made by 3D printers too. As a model for artists, it probably cannot be surpassed.

|

Victoria Hinshaw, Author

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed