|

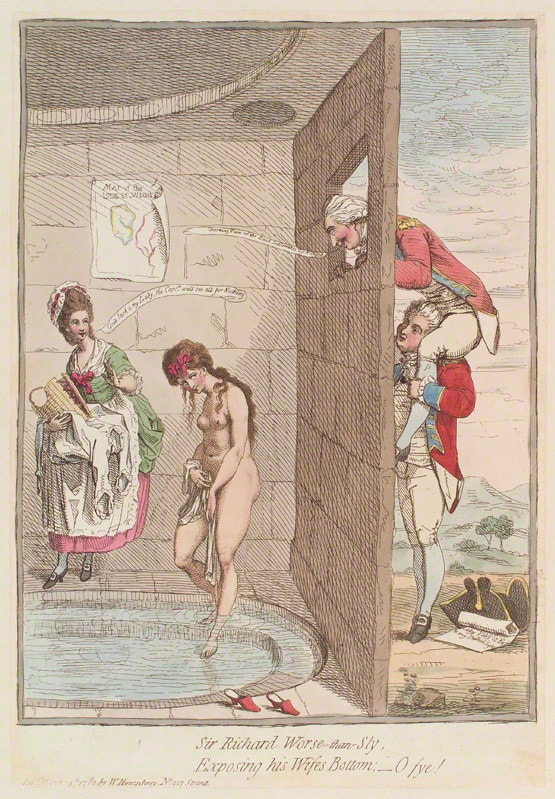

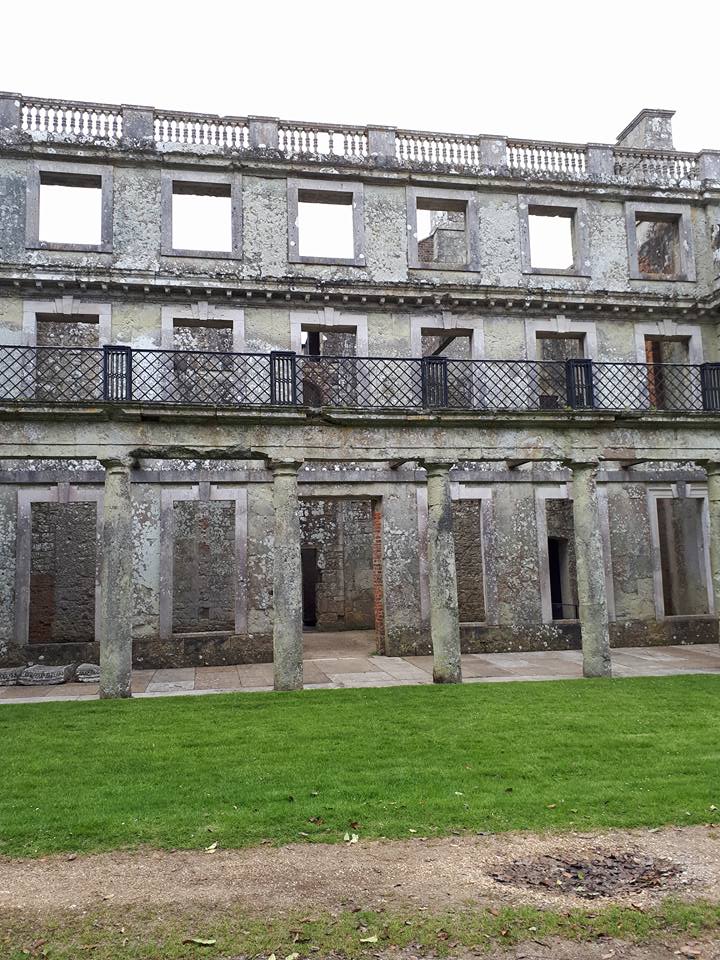

Recently I have visited a couple of houses which illustrate dramatically the decline and ruination of many English Country Houses. Here is the first of several posts on these spots. For many years, I have wanted to visit this site, a preserved ruin of a lovely country house fallen into the fate of so many of its fellows among stately homes. Kristine Hughes Patrone and I had come to the Isle of Wight primarily to visit Osborne House, a residence of Queen Victoria and her family. But we decided we must see this famous ruin, so we set off on a bus ride around the Isle, driving through picturesque towns, villages, and the countryside. When the driver told us we had reached the proper stop after an hour or so, we got off and followed the signpost toward English Heritage's site. Off we trudged up the road, past a farm or two, empty fields and lots of friendly cows. Remember to click on the photos above for full size versions. It was a long hike, in my opinion, but worth it. Eventually, after several hills and amidst lovely bluebells in the woods, we saw it. There wasn't a soul around. A small carpark was empty and a closed building that apparently held an office stood at the edge of the premises, but no evidence of human company showed. The silence seemed suitable, correct for the shattered elegance of the noble structure, stripped of almost all its accouterments. It was not spooky, but merely sad, with the world having passed it by. Once, it seemed to say, I was magnificent. Originally a priory, the property was the home of the Leigh family in the Elizabethan era. In 1702, Sir Robert Worsley began a new building on the site which was extended in the 1770's by his heir, Sir Richard Worsley. You can see from the photo above that it has been stripped of all furnishings except for one room. Here a room was enclosed and roofed; these portraits and a text panel told the sad story of the house and its ill-fated occupants. On the left is Sir Richard Worsley, (1751-1805). 7th Baronet of Appuldurcombe, copy of a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1775. On the right is Seymour Dorothy Fleming, his wife Lady Worsley (1758-1818), a reproduction of the painting by Reynolds, now hanging in Harwood House, Yorkshire. They married in 1775. The very unhappy marriage led to a Crim. Con. case in court, and wild stories resulting in such caricatures as this 1782 Gillray cartoon titled "Sir Richard Worse-than-sly, exposing his wife's bottom, o fye!" Eventually they separated permanently and took up with others. The beautiful house remained until after World War II during which it was used by the military. A German explosive destroyed the roof and it was never repaired. After the hostilities ended the interiors were removed, leaving only a shell. And so it remains. Supposedly it is haunted but on the beautiful May day we visited, all we met were blossoms. If you are in the market for a fixer-upper, English Heritage might be willing to deal!

0 Comments

The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art was a treat to visit, a treasure-house full of objects from many centuries worldwide. It has two adjacent buildings. The columned original was opened in 1933; the Bloch Building, housing contemporary art opened in 2007. For my purpose here on this blog, I will look primarily at British Art from the 19th and 19th centuries. But first....the exterior. Below, left the original building combining neo-classic and art deco styles; at right, the white structure of the Bloch building. Within there is a wide contrast in styles; in this court, the pillars frame fine Brussels tapestries from the 17th century.You can see the back of The Thinker by Rodin in the middle overlooking the broad lawn and sculpture park. The classical urn is a perfecct foil for the shuttlecock by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje von Bruggen, one of four in various positions in the park. The stairwell in the "old" building, which dates from 1934. Kim Wilson and I prepared to wear our feet to bluddy stubs as we tried to cover every gallery. The Courtyard houses a lovely cafe where we refreshed our energy. Among the N-A's treasures is this marble lion from Greece, 325 B.C.E. And now, as promised to some of the British works. John Hoppner (1758-1810) painted Portrait of Lady Emily St. Clare as a Bacchante in 1806-07. She was an actress and the mistress of Sir John Flemming Leicester who commissioned many artists to paint her. Hoppner painted many aristocrats including all of George III's daughters. Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) painted Mrs. William Lock of Norbury in 1829. Lawrence was the best known portraitist in Europe in the early 19th century. His subject here, Frederica Augusta Lock is obviously prosperous and a credit to her husband, whose portrait hangs int he Boston Museum of Fine Art, also executed by Lawrence. The Locks had numerous children, and most were both amateur painters and collectors of art. Among the Nelson-Atkins collection of miniatures is this portrait of King George IV in 1821 by Henry Bone (1755-1834), enamel on copper. Repose, c.1777, by Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) shows a rustic landscape. The text panel says,"Thomas Gainsborough evoked the hard labor of the rural poor while also representing the landscape that provided a source of prosperity for the painting's wealthy audience." Gainsborough is probably best known for his elegant portraits of the aristocracy. Among the many portraits is Henry Raeburn's (1756-1803) image of Master Alexander Mackenzie, 1822. Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) was a master of the play of light. In Fish Market, 1810, he portrays the beach in Hastings where the fishermen display their wares for shoppers. John Constable (1776-1837) was moving towards Romanticism with his work, The Dell at Helmingham Park, 1830. Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797) pictures a scene in the Lake District, Outlet of Wyburne Lake, 1796. This is Wright's last known painting.

The Stately Home on the site was formerly the Great Gatehouse of Beaulieu Abbey, founded in 1204 on land gifted to the Cistercian order by King John. The springtime blooms of the rhododendrons and other flowers were spectacular. Please click on the pictures for full-size versions. Above, in the Topiary Garden, the Mad Hatter's Tea Party and the Cheshire Cat. The Portrait Gallery, below, exhibits portraits of the various dukes and barons whose families owned the estate from the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII in the 16th century. In actuality, the estate has been in the hands of one or another branch of the same family since 1538. Below, Walter Francis Montagu-Douglas-Scott, 5th Duke of Buccleuch (1806-1884), who presented the Beaulieu estate to his second son, Henry John Douglas-Scott-Montagu, 1st Baron Montagu of Beaulieu (1832-1905), ancestor of the present family in residence. Below, the Lower Drawing Room, added in the Gothick style the 19th century, reflecting the monastic origins of the building. Below, the Dining Hall, also a Victorian remodeling. At one end of the Dining Room, the children's table was visited by someone's favorite mount. Above. views of the Victorian kitchen, where treats for visitors were in the oven. The Upper Drawing Room carried on the Gothick origins and style. Formerly it was a chapel for visitors to the Abbey. The piano is an English-made Broadwood. The family Dining Room. The Family Library aka The Late Lord Montague's sitting room ...comfortable in all respects. Miniature stage set and enviable shelves of book. Let me at 'em. The hallways are often the sites of a familiar scene in stately homes -- trophies of past conquests, which often do not appeal to my tastes in sport. Nevertheless, it was a lovely adaptation of an abbey turned family home.

|

Victoria Hinshaw, Author

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed