Another amusing American connection is the fact that H. Gordon Selfridge, who founded the great department store on Oxford Street, leased Lansdowne House in the 1930’s before it suffered its partial demise. Selfridge was born in Wisconsin and was an executive with Marshall Field & Co. in Chicago before he moved to England. During Selfridge’s tenure, the house was the scene of many famous parties, most attended by his intimate friends, the celebrated dancing Dolly Sisters.

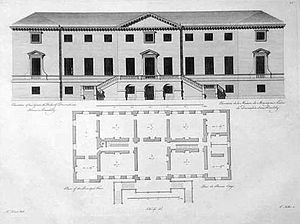

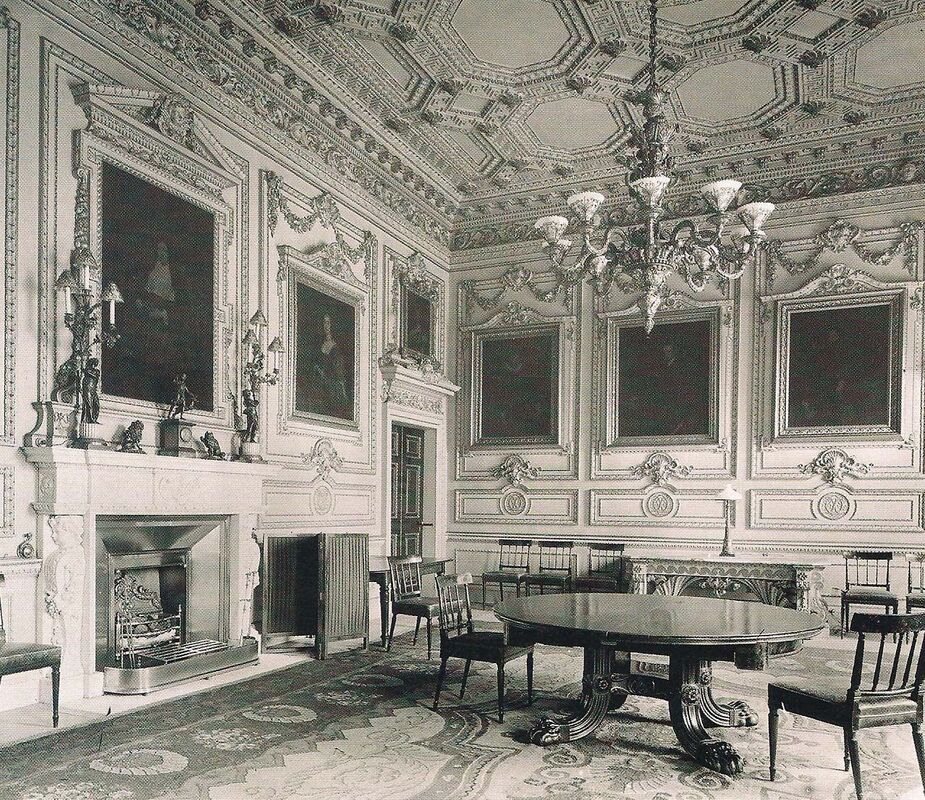

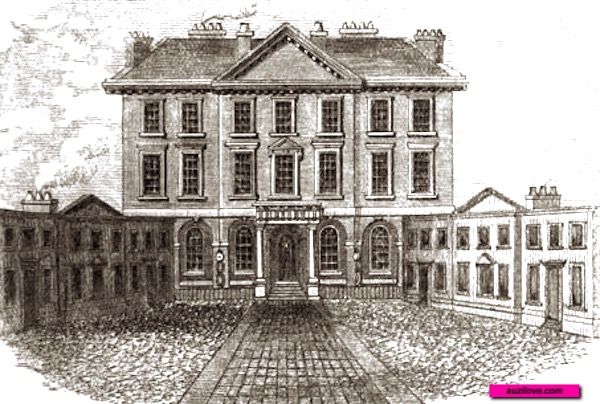

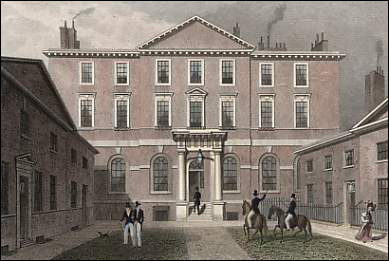

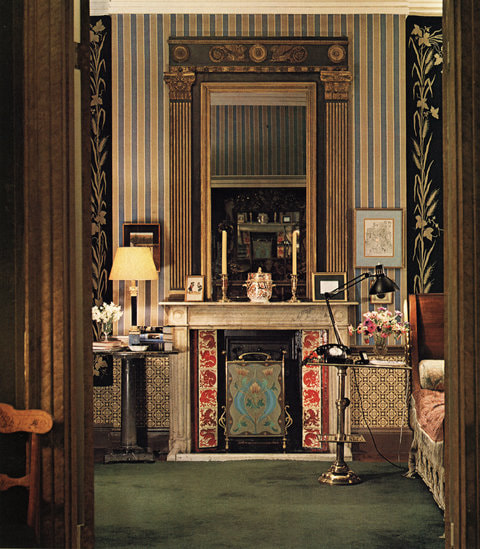

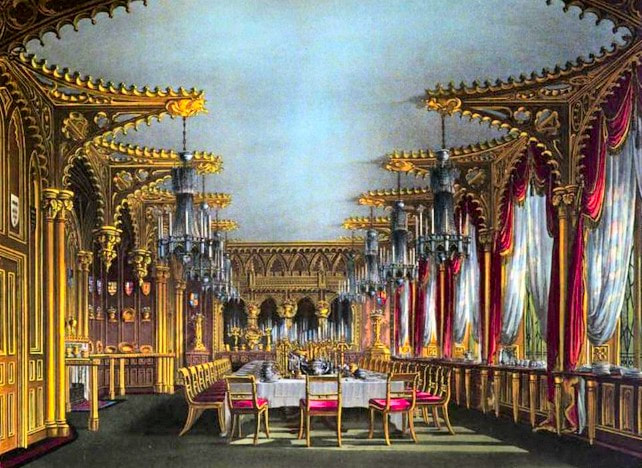

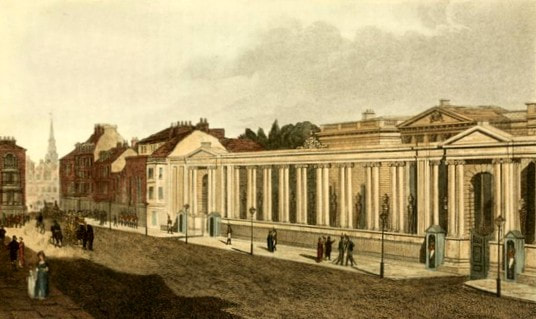

Below, at left, Bowood from Morris's County Seats, 1880. The remaining Orangery is on the far left, and the house on the right is gone. Right, the Bowood Dining Room, used by the Council of Lloyd's of London.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed