|

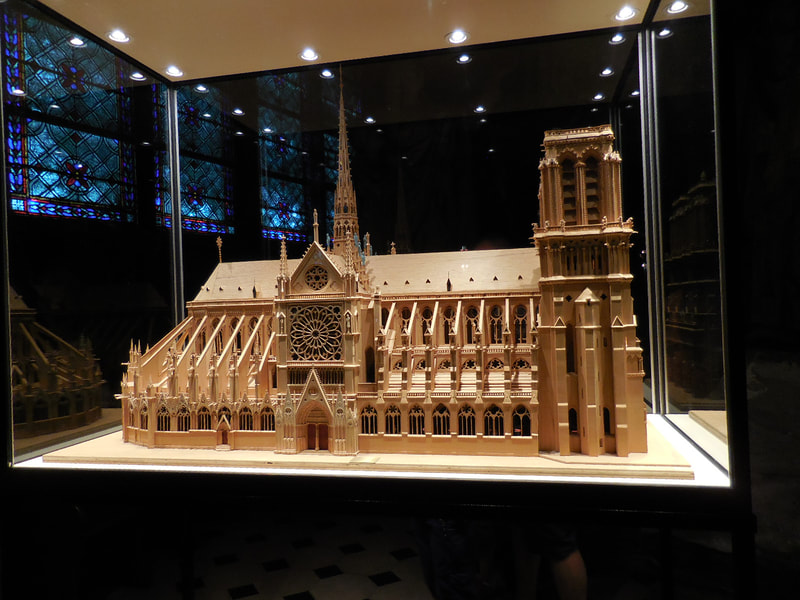

Last winter, we were at the beautiful white sand beach in Naples Florida on April 15, 2019, when our phones lit up with the horrifying news that Notre-Dame de Paris was on fire. Immediately my thoughts flew to my first visit there many years go. I recalled the awe with which I wandered around the great cathedral, entranced by its ancient spiritual aura, beyond religion to the deepest, most mysterious meaning of life. The sounds of the cathedral contributed to my reverence, for most of the voices spoke in languages I hardly understood, in Latin or in French...and in a way I never appreciated before, the very incomprehensibility (I hope that is a word) created a solitude in me that enhanced my emotional reactions. I have never forgotten that experience. When we returned home from the beach, we switched on the tv and of course were immediately immersed in the tragedy in Paris. Even the grandchildren were engrossed by the pictures and commentary. We watched the intricately carved wooden spire burn and collapse, over and over again. As the days passed, we were all pleased to hear Notre-Dame would be restored and/or repaired. Some places were not as severely damaged as once feared. Compare the pictures below with the first picture from my visit in 2014 at the top of this blog. Nevertheless, the damage was horrendous. Rose windows and other stained glass creations were mostly saved. When I returned from Florida to Milwaukee I scoured my picture files for views of Notre-Dame. I even found a few old slides from the days of 35 mm. Kodak camera. Below, a few of the more recent shots, from a steamy day in Paris in 2014 when the Cathedral was delightfully cool, though crowded with visitors. Nevertheless, I managed lots of pictures without a soul in evidence. I wonder if the wooden model was saved? I wonder if I will ever see Notre-Dame de Paris completed? Since I spend my time aboard mostly in England, perhaps not...but I have my memories. A bientot!

0 Comments

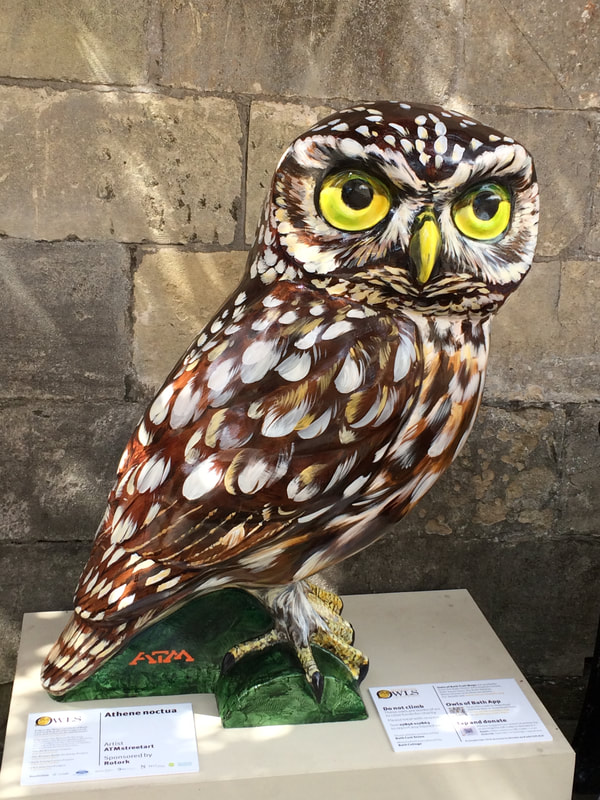

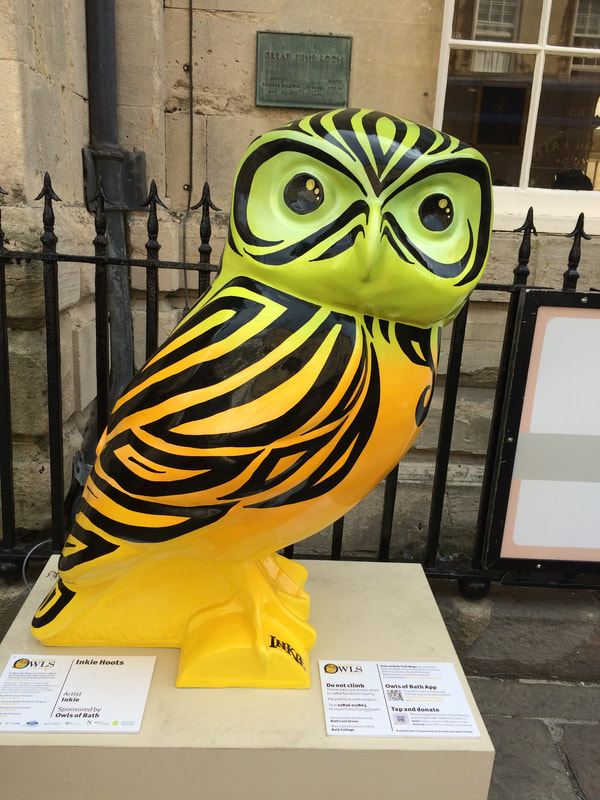

What does one do in Bath? Why bathe, of course. The Cross Bath, by John Chessell Buckler around 1825 This print shows the Cross Bath as it looked in the late Georgian era. This view of the Cross Bath and Bath Street is by John Claude Nattes, dated 1804. Below, the Cross Bath in July, 2018, back in operation as part of the Thermae Spa. Below, another facade of the Cross Bath In today's Bath, it is once again possible to enjoy the waters of the hot springs at the Thermae Bath Spa. View the video. Thermae Spa video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F6Ny0MbxS4Y "There are three separate springs in Bath, the largest and most significant is the King’s Spring which rises within the Roman Baths Museum. The smaller Hetling Spring and Cross Bath Spring are located approximately 150 m to the west of the King’s Spring. The thermal spring water emerges from funnel-shaped gravel deposits under the city. Each spring is tapped at depth by a borehole, which draws water from below the shallow gravel deposits to deliver clean thermal water to the drinking fountain in the Roman Baths museum and the local spa complex." Above, the fountain for drinking the mineral-rich spring water in the Pump Room. Returning to the Therme Spa, I had a wonderful morning in the pools, and I have to admit, I felt great. The placebo effect? Perhaps, but I'll take it. Highly recommended if you are in Bath. I was definitely invigorated! Below, since pictures are not allowed inside, for obvious reasons, this is from the website. It perfectly captures the ambiance of the open-air pool. Above, the statue of Bladud overooking the Kings Bath. The legend of Bladud’s pigs and their miraculous recovery from skin disease after wallowing in the mud near hot springs is renowned in the history of the city. How true is it may be questioned, but claims that Bladud, once hailed as a prince, thus cured himself of leprosy and founded the tradition of bathing in the hot springs is too delicious to be forgotten. The truth is lost in the mists of times, but has endured since the first century BCE. Below, the Roman Bath. All those who came to Bath—Celts, Romans, Saxons and everyone—believed the waters were helpful whether bathed in or drunk from a cup. The Romans turned the city into a luxurious spa, the remains of which are a major tourist attraction. Wikipedia supplied this intelligence: the “word SPA is associated with the Latin phrase ‘Salus Per Aquam’ or ‘health through water’.” Drop that at your next appointment for a massage. Below, a Georgian period view of the King's Bath outside the pump room., by Thomas Rowlandson, 1798, from Wikipedia. After the Romans left Britain, the springs were gradually forgotten and buried. However, the water continued to flow and by the 17th century, its healing properties were rediscovered. During the 18th century, Bath grew in importance, in beauty, and in the celebration of pleasure. All of this was based on the treatment of almost any complaints people could imagine and the existence of all kinds of care, from quacks and snake oil salesmen to doctors who actually studied medicine. Below, Hospital of St. John the Baptist, Founded 1174, an alms house still in operation. Below, the Royal Mineral Water Hospital, built 1740's. Its current status is pending, until recently a part of the National Health Service, but perhaps undergoing some changes. I found reports the building was for sale, but not further word. If you have followed my meandering posts on my week in Bath in July 2018, you my have noticed the colorful owls here and there on the streets. A public art sculpture project, 82 Minerva's Owls were decorated and stood in Bath until auctioned off in September 2028, bringing over £ 140,000 for local charities. Below, few of my photos, while hooting farewell to Bath, for now. And why Minerva's Owls, you might ask. That dates back to the Romans, whose goddess of wisdom was Minerva.= and her symbol was the owl, known from prehistory as a source of wisdom. The earlier Celts had dedicated the springs to their goddess Sulis. The Romans simply merged the two into Aqua Sulis, a shrine to Minerva.

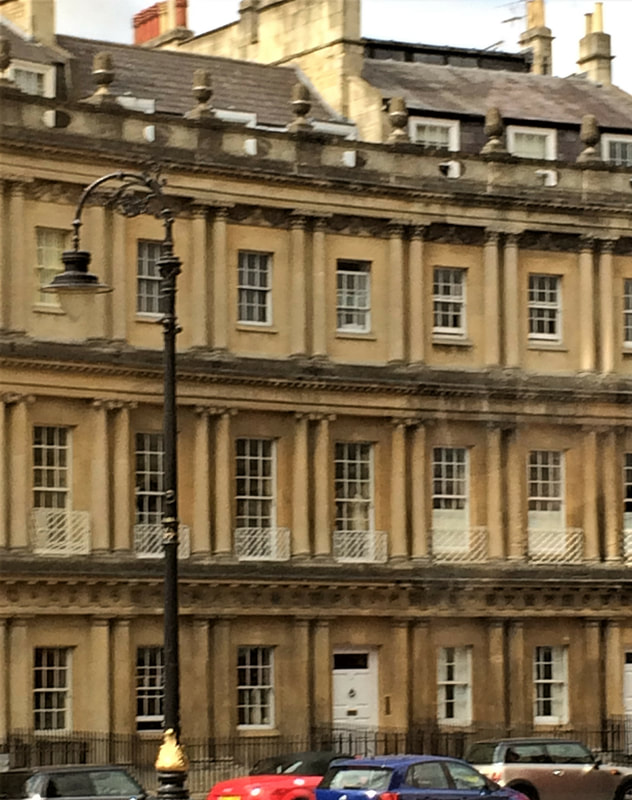

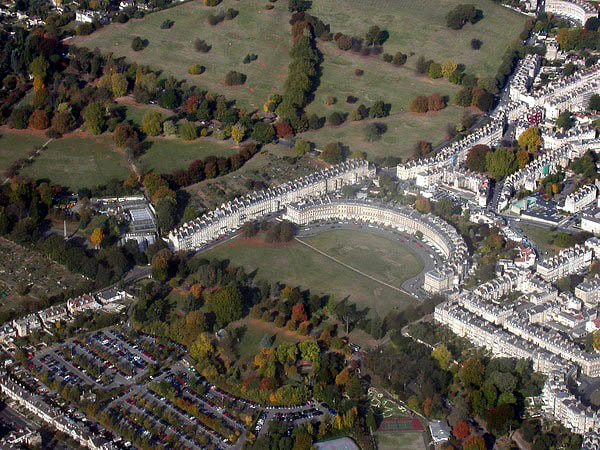

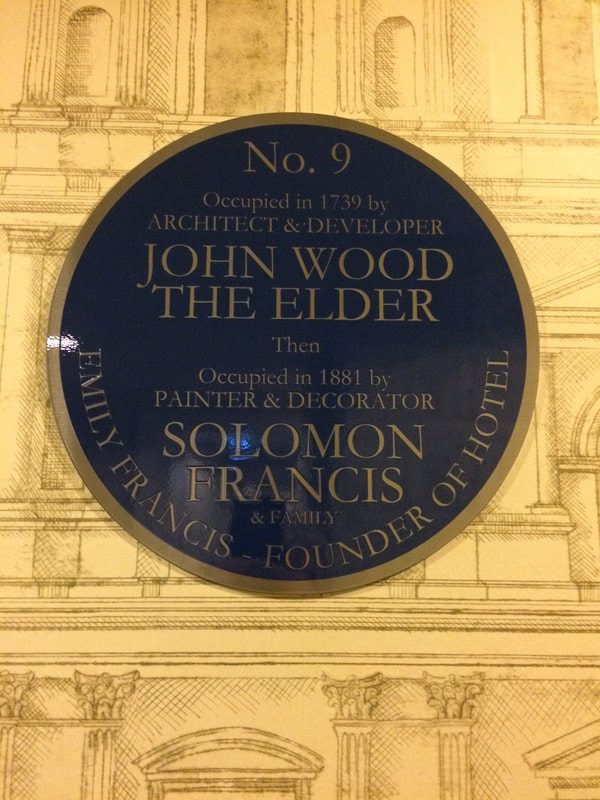

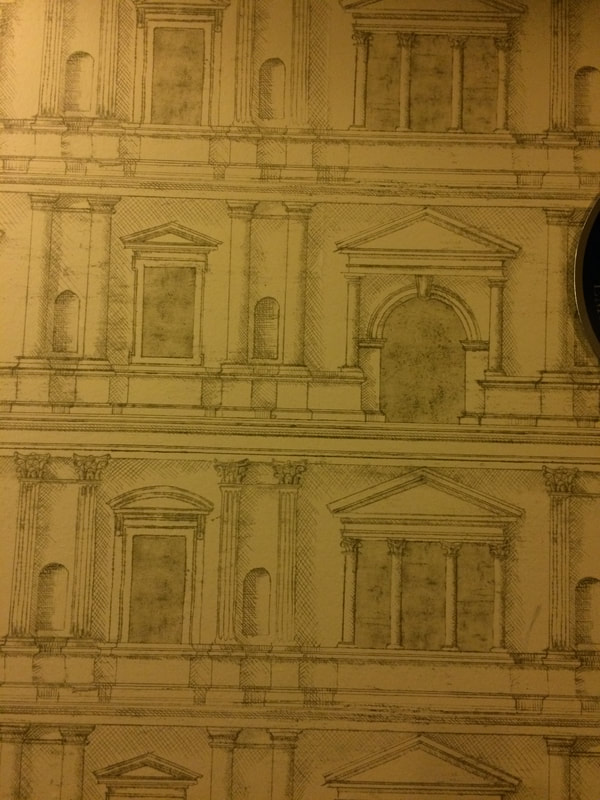

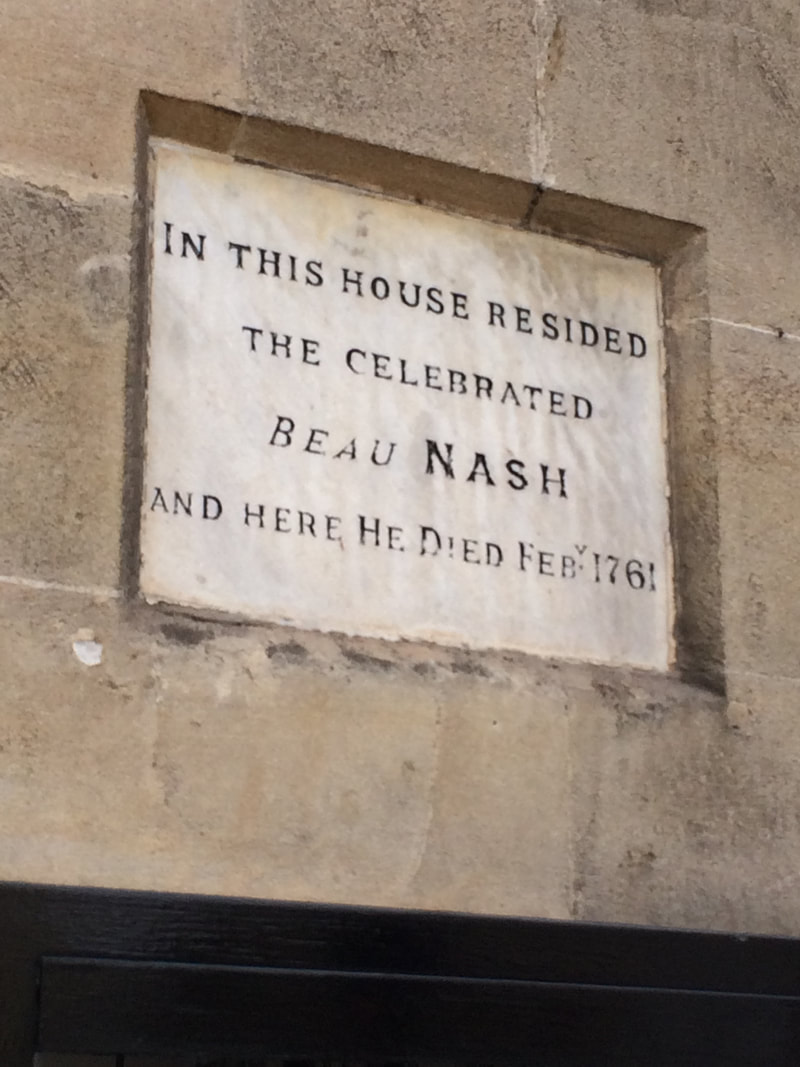

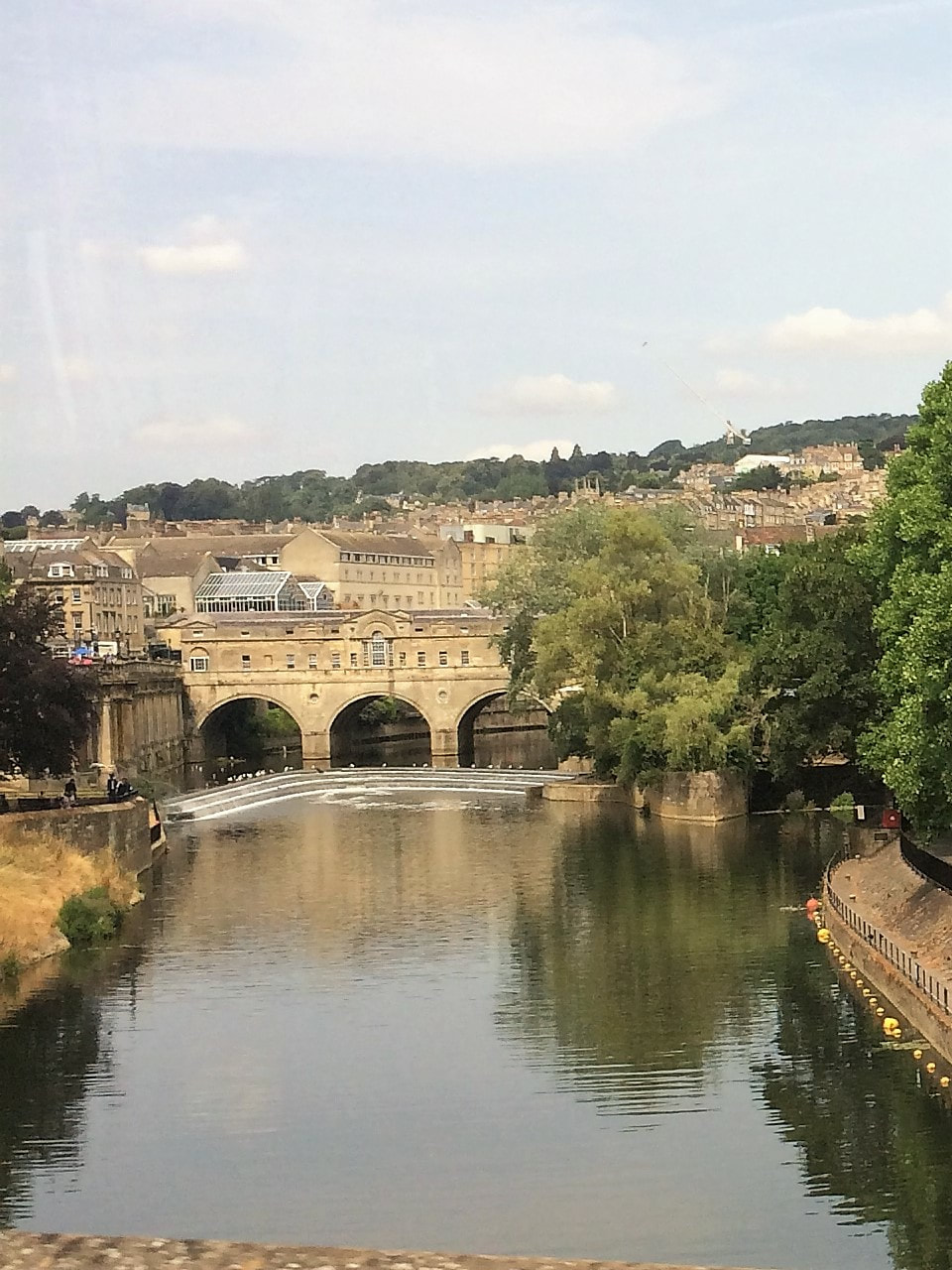

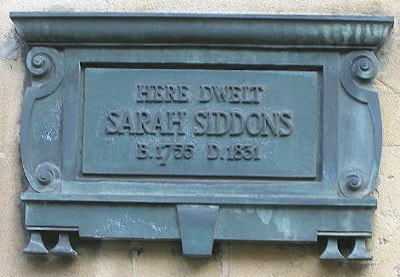

Below, a gilt bronze head of Sulis Minerva found in Stall Street in 1727 and on exhibition at the Roman Baths, photo via Wikipedia. Here are some random views of Bath, pictures I love to look at!! Unless otherwise noted, I took the photographs. I spent a week in Bath in July 2018 at the end of the JASNA summer tour of England. I stayed at the St Francis Hotel in Queens Square where I completed a writing project as well as wandering at leisure around the city. I had visited before, but always seemed rushed. So taking my time and really enjoying the city was a great pleasure. Bath is a UNESCO World Heritage City, celebrating the amazingly unified and harmonious architecture and the city's position in the Georgian society to which it catered. Above, the Assembly rooms (at the lower left) and the Circus, photographed from a balloon by Roger Beale, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44942471 Above and below, the Circus. Note the three orders of columns, ground level: Doric; above, Ionic; top, Corinthian. And along the roof line, a series of stone acorns. The dry grass was the result of a very hot and dry summer in 2018. Ignore both the grass and the autos if you please.  This Stone Acorn was taken from the parapet of the circus, created about 1760. The label in the Museum of Bath Architecture reads, "By placing acorns along the top of the Circus, John Wood was making references to both Bladud (the mythical founder of Bath who discovered the healing hot waters), as well as to the Druids, who were the 'Princes of the Hollow Oak'...The Circus...inspired by ancient stone circles." This aerial shot of The Royal Crescent (Photo by Jonathan Lucas - English wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6187720) shows the elegant sweep of the lawn and the graceful curve of the terrace of houses. Eliminate the cars and paving, add some green to the grass, and you can easily see the unique qualities of the Royal Crescent in 2018, above, and in old prints below. The Royal Crescent was built by John Wood the Younger, begun in 1767 and completed in 1775. Comprised of 30 individual houses, it is five hundred feet long with 114 Ionic columns. Note that however harmonious and identical the facades appear in the front, the backs of the buildings vary greatly. It is something of a shocker when you walk around to the back, as you can see in this picture from wikipedia. Here is another aerial photograph showing the Circus and the Royal Crescent in relationship to one another, down one short stretch of Brock Street. The photo is by M. Caine http://www.icons-multimedia.com Queen's Square, built by John Wood the Elder, was begun in 1728 and completed in 1736. Visit Bath writes, "It marks the beginning of his development of the upper town and is a key part of the formal grouping with the Circus and the Royal Crescent.The focal point of the square is the obelisk, with its inscription by Alexander Pope. It was erected by Beau Nash in 1738 in honour of a visit by Frederick, Prince of Wales. The obelisk used to have a needle point, but it was blunted after being struck by lightning in the 1830s." Queen Square is a popular meeting point and often filled with students, tourists, children, and other residents. The north side of the square, No. 24, is now the office complex of a firm of solicitors and its elegance has been entirely preserved. Queen Square, north terrace, by William Watts in 1819, Victoria Art Gallery The elegance continues around the square, and here you would find another firm of solicitors. And below, the South side of Queen Square where the St. Francis Hotel was my home away from home. On the interior walls, the wallpaper honored the local architecture and the architects and residents of the building. Just south of Queen Square, I noticed this. The Beau Nash House is now an Italian Restaurant (very good food, BTW). Richard Nash (1674-1761) was the Master of Ceremonies in Bath for many decades and as responsible as any other individual for the growth of the city as a fashionable Georgian destination. When I first beheld Bath, I thought the building in the picture below was a travesty. Now known as the Empire Hotel, it was then, decades ago, blackened with years of soot, one of the dingiest of the Victorian monstrosities found all over England -- certainly it did not belong in Bath. It was built in 1899-1901, as a hotel, and such it remained until 1939 when it was taken for the war effort by the Admiralty. Were they to launch aircraft carriers on the Avon? Reports say it was used to sort postal materials. After 1995, when it was given up by the government, it was restored, cleaned and turned into apartments and hotel accommodations, achieving Grade II listing. I still think it sticks out like a sore thumb in Georgian Bath, but there it is, hard by the graceful Pulteney Bridge designed by Robert Adam.  Robert Adam's design has been more or less preserved over the years through various alterations and restorations to the Pulteney Bridge since it was built in 1774. Below, as pictured by Thomas Malton in 1785. The Weir was constructed in 1968-82 on the river Avon. The far side of the bridge becomes Great Pulteney Street, lined with terraces of homes of Bath stone. Below is the view from the opposite end, in the Holburne Museum in Sydney Gardens. Views, below, of Great Pulteney Street and the fountain at Laura Place. The fountain was an addition to the street in the late 19th century. Below, an 1812 print of the Paragon. Jane Austen's aunt and uncle, Mr and Mrs. Leigh-Perrot (she of the supposedly stolen black lace), resided in The Paragon at #1 from 1797-1810. The famous actress Sarah Siddons (1755-1831) lived in one of the houses in the Paragon, #33. She was born into the distinguished family of theatrical stars, the Kembles, and was particularly famed for her role as Lady Macbeth.  Sarah Siddons House 33, The Paragon In the middle of The Paragon stands the Museum of Bath Architecture. It occupies the former Countess of Huntingdon Chapel. Lady Selina Hastings (1707-1791) built the chapel in 1765, one of the 64 Methodist chapels she created in Britain. The chapel, in Gothic revival style, is unusual in Bath. Lady Huntingdon, a friend of Horace Walpole, was a leader of evangelical and philanthropic causes. The museum's displays all related to Bath's buildings, and provide text panels about their construction. Please click on the photos for larger versions. What have I left out in my survey of Bath buildings? Why the baths, of course...coming soon.

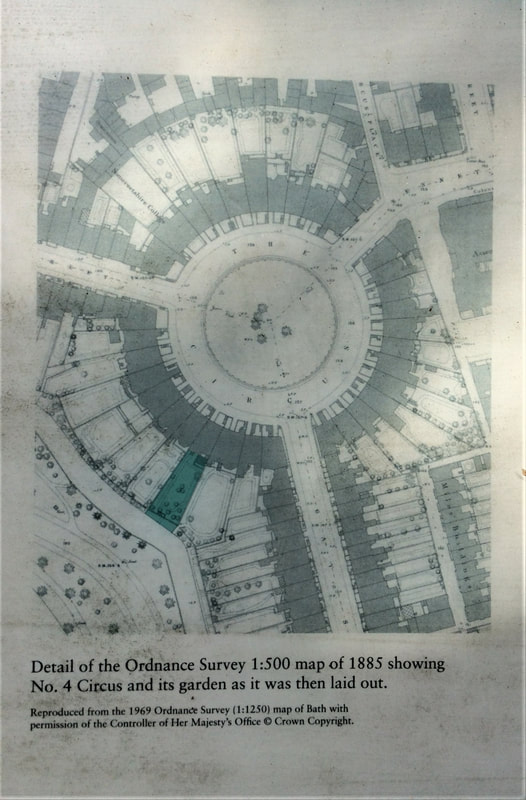

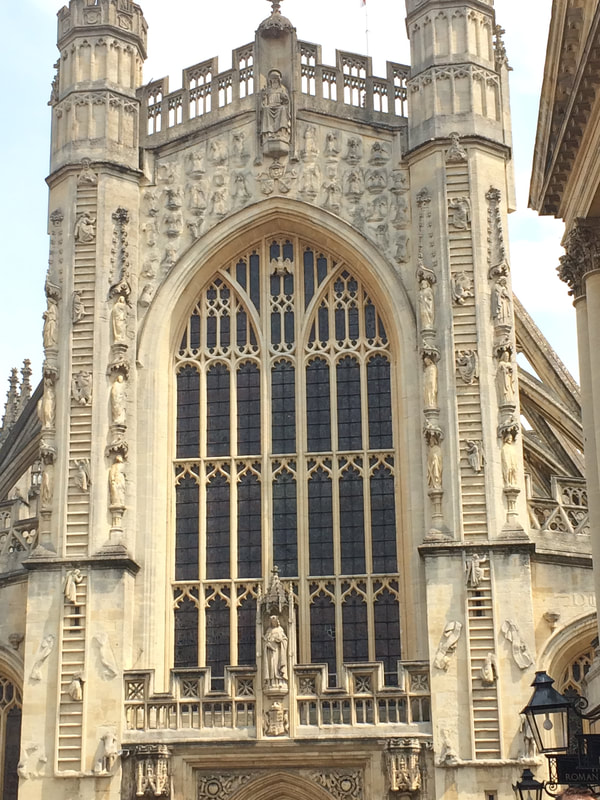

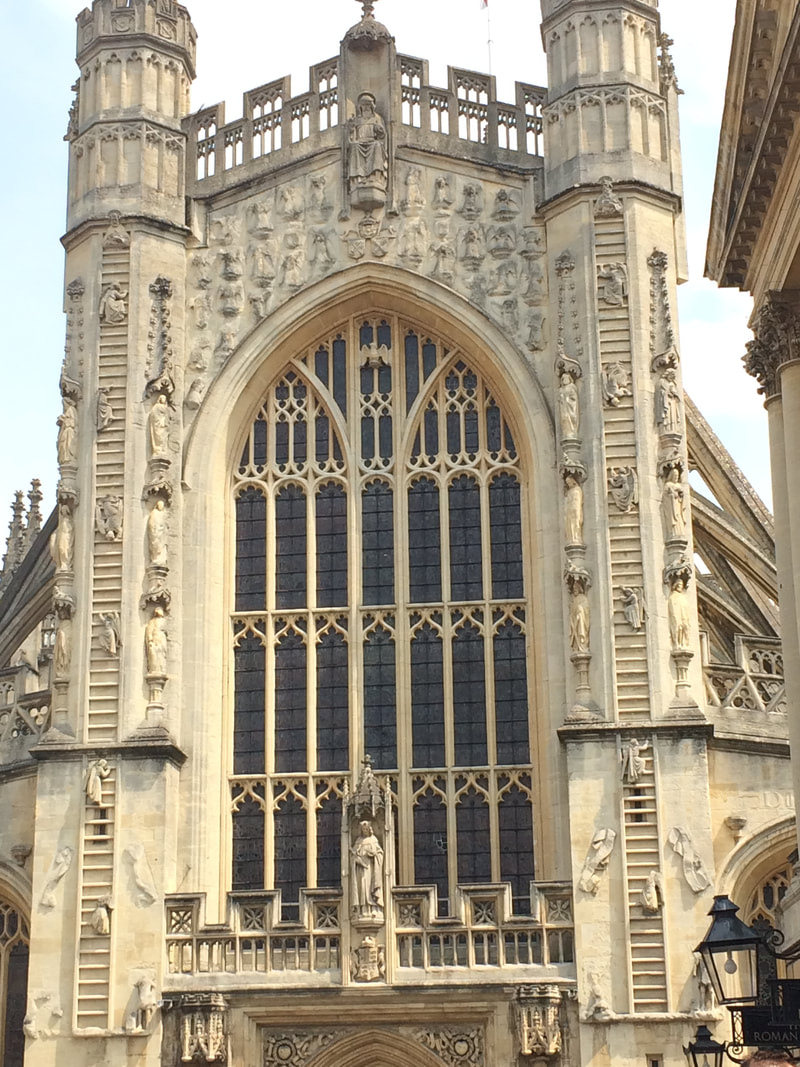

What have I left out of my long list of posts on Bath? Let's see. Architecture, Bits of History, Art Museums, Jane Austen, No. One Royal Crescent (see in the Archives August 8, 2018). But I haven't covered the Georgian Garden. Or my evening at the Theatre Royal. Or my relatives in the Bath Abbey.Thus the three subjects of this post. The Georgian Garden is found behind #4, The Circus, access from a gravel walk leading from the Royal Crescent to Queen Square. The plan is similar to the original garden laid out after the completion of the house in 1761. Flower beds and gravel form a design chosen to be viewed from the house. Though July, 2018, was very hot and dry, the garden was full of blooms. And a roller was left behind to show how it was maintained. One of the first things I noticed when I arrived in Bath in July 2018 was a poster for the performance of Oscar Wilde's play An Ideal Husband at the Theatre Royal. I rushed right off to the box office, mere yards away from my hotel, and got a ticket. What a treat to see the Foxes -- and Susan Hampshire, Fleur in the long ago version of The Forsyte Saga on Masterpiece Theater. The play was a delightful romp, with a contemporary message, of course, honoring the value of honesty and ethical behavior. I was sure I remembered a memorial in Bath Abbey from a previous visit, a name similar to my married name. Certainly had to take another look. Scads of visitors crowded the plaza between the Abbey, the Roman Baths and the Pump Room. And many filled the Abbey. And there they were, a branch of the family that used the English spelling Henshaw, while the branch I married into followed the Anglo-Irish version Hinshaw. If I remember correctly, the American Hinshaws arrived in the North Carolina foothills in the 17th century, but perhaps Jonathan and Mary were their distant cousins. Adieu, Bath!

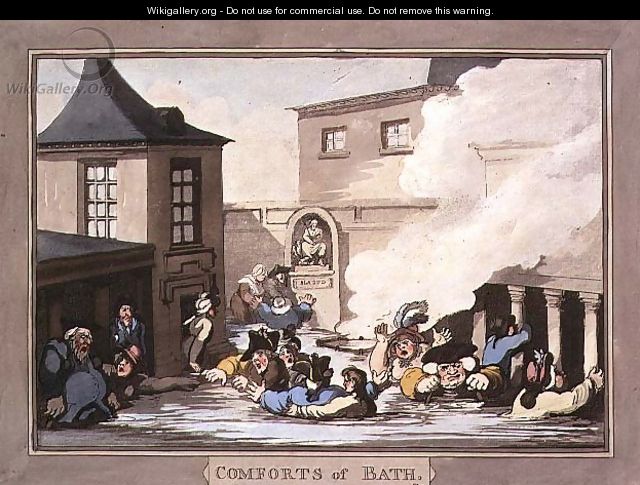

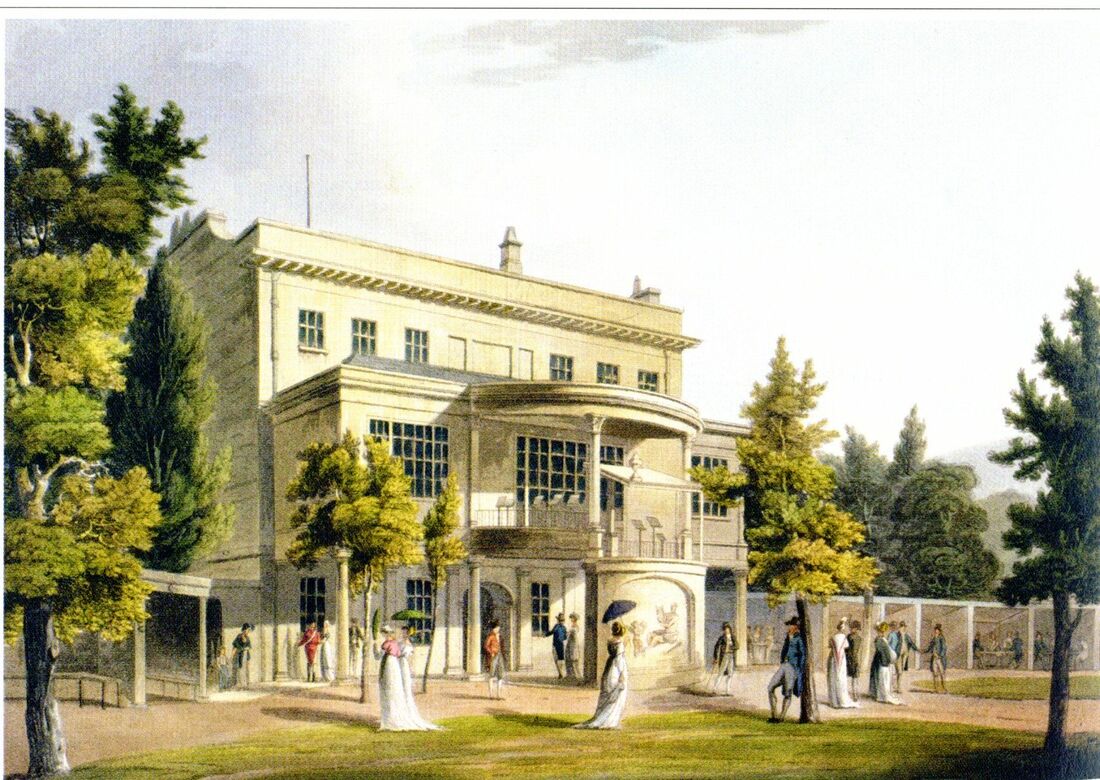

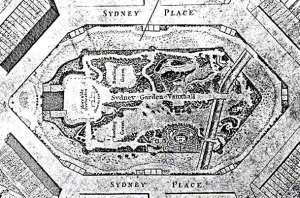

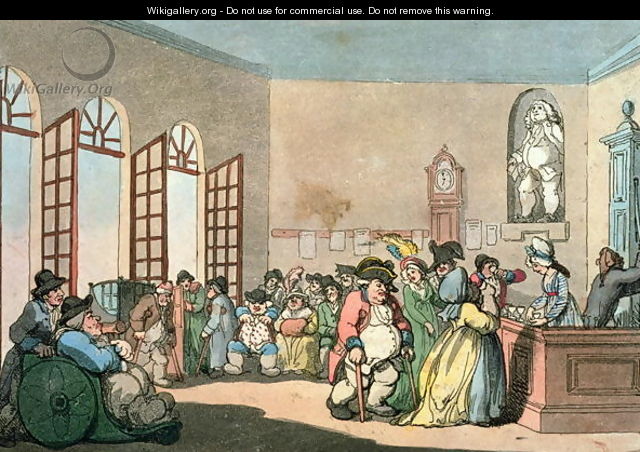

Jane Austen (1775-1817) visited Bath several times before her family moved to the city in 1801. She is widely believed to have disliked the city, though some scholars disagree. They believe she appreciated the lively social life she enjoyed in Bath. Jane Austen spent time here at No. 13 Queen Square with her mother and brother Edward in 1799. #1 Paragon, which may be where Jane's aunt and uncle Mr. and Mrs. Leigh-Perrot lived, though I understand the houses may have been re-numbered. Jane and her family stayed with their relatives when they first moved to Bath in 1801 while they looked for a house to lease. One assumes the street repairs were less colorful back in the day. No. 4 Sydney Place, where Jane Austen, her sister Cassandra and her parents lived in Bath from 1801-1804. The house was directly across from Sydney Gardens, a pleasure park with the Sydney Hotel, now the Holburne Museum, the site of many social activities. Breakfasts were served, as well as evenings with the trees lit by hundreds of lanterns. Below, the plan of the pleasure garden, 1810, generally following the example of London's pleasure gardens. The original name was Bath Vauxhall Garden. Jane was known to be a keen walker so she probably enjoyed outings in the Gardens as well as all around the Bath region. The Pump Room is pictured in 1804 in a print by John Claude Nattes. Everyone in Bath visited the Pump Room to drink from the King's Spring and to exchange pleasantries and gossip in an informal social setting. It is lively today, probably quite different than it was in Jane's era. Now the pleasantries are likely to be centered upon tea and cakes while the visitors come from all over the planet and would not know each other, much less be able to share local gossip. Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1807), below, from wiki gallery, dated 1798 from The Comforts of Bath, his series of comical drawings of the city and its visitors. Milsom Street in Jane Austen's day, above and photos from 2018, below. Everyone in Bath shops in Milsom Street, including the characters in Persuasion and Northanger Abbey, two Austen novels with many scenes set in Bath. When Jane Austen attended balls in Bath, she could go to either the Lower or the Upper Rooms where social events were held. However, the Lower Rooms which overlooked the Parade Gardens, had disappeared by the 1930's. The Assembly Rooms, now run by the National Trust, were opened in 1771. The Assembly Rooms in 1818, looking much the same as they do two hundred years later in 2018, below. The Assembly Rooms can be visited most days. After years of neglect and damage in WWII, they were restored to their former opulence, The Fashion Museum occupies the lower level. Bath Abbey has been standing in the city since the 7th century. Once part of a Benedictine monastery, it has been an Anglican church since the time of Henry VIII. It is a dominating structure in central Bath, but I could find no evidence Jane Austen ever worshiped here, or indeed, even visited though it seems inevitable that her curiosity would have led her inside. Perhaps the Austens worshiped at St. Swithin's Walcot, the site of an older church where Reverend Mr. George Austen married Cassandra Leigh in 1764. The present church was built a few years later, consecrated in 1777. Its churchyard is where Rev. Austen is buried. Time has worn away most of the inscription on the gravestone of George Austen, 1731-1805. The plaque below helps the visitor. More wanderings in Bath are in store for this blog, soon.

|

Victoria Hinshaw, Author

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed