|

Greeting us as we arrived at the estate in Staffordshire was the distant Hadrian's Arch, built in the 1760's. It is one of many follies built on the grounds in the fashion of the times.The guidebook of the Shugborough Estate, now a National Trust Property, tells us: "The story of Shugborough today begins with two brothers, Thomas and George Anson, who were born at the end of the 17th century." Above, left, a portrait said to be Thomas Anson (c.1695-1773); right, Admiral George Anson (1697-1762) painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1755. They were the sons of William Anson, whose ancestors had acquired the estate in 1624. When George died, Thomas inherited the large fortune the Admiral had acquired during his naval career. Thomas Anson died unmarried in March 1773; the Anson estates went to his nephew, George Adams (1731-1789) who took the name Anson and was the ancestor of the Earls of Lichfield. George Adam-Anson's son, also named Thomas (1767-1818), took over the estate in 1789 as well as his father's seat in the Commons. In 1806, he was named 1st Viscount Anson/ Above, the Ionic portico facade of Shugborough Hall, September, 2022. Below, the garden facade. Thomas Anson married well, a daughter of the famous agriculturalist Thomas Coke of Holkham Hall. Ann Margaret Coke was also a talented artist; in 1799, she painted The Three Children, the eldest of her eventual eleven children. The boy on the left, Thomas William Anson, later became the 1st Earl of Lichfield. Below, among the guests entertained in the Red Drawing Room was the teen-aged future Queen Victoria in 1832. The chandelier is particularly lovely. Click on the small pictures for larger versions, please. The earlier Thomas Anson (c.1695-1773), expanded the house, commemorating his scholarship and his Grand Tour in the Drawing Room, below. The portrait is his brother Admiral George Anson, 1st Baron Anson, by artist Thomas Hudson c. 1747. The paintings are Capricci, (singular form: Capriccio), architectural landscape paintings portraying a fictional combination of imaginary buildings. Most hung here are thought to be been the work of Pietro Paltronieri (1673-1741) of Bologna and were commissioned by Thomas Anson for this drawing room. The rococo plaster work ceiling frieze, coved ceiling, overmantel, and carved picture frames were probably designed by Italian stucco artist (stuccadore) Francesco Antonio Vassalli around 1748. Below, left, the central ceiling panel was inspired by Guido Reni's 1614 painting 'Apollo and the Hours preceded by Aurora' in the Palazzo Rospigliosi in the Casino Pallavinci in Rome. Center row, more views of the Drawing Room. Above, left. plasterwork decoration on the fireplace. Right, the elaborate clock matching the title panel for the portrait. Below, examples of the capricci, especially admired by a copyist. Other scenes, below, from the handsome rooms and gardens of Shugborough House. Of special note, center row right, a magnificent mahogany china cabinet by Chippendale which holds some of the objects brought back by Admiral Anson from his globe-circling voyages. Sadly, in 1842, many of the family's treasures were sold at a two-week sale to cover the debts of the 1st Earl of Lichfield (1795-1854). Below, a few of the monuments and follies which decorate the grounds. Top row, left, a faux ruin, and right, the Tower of the Winds. Lower row: The Doric Temple by James 'Athenian" Stuart, left, and the Cat Monument, c. 1770, executed in Coade stone. The pictures and descriptions in this blog post merely scratch the surface of all the attractions to be experienced at Shugborough Hall. I have not mentioned the apartments of the late Patrick Lichfield (1939-2005), fifth Earl and a famous society photographer, whose apartments in the house are open for viewing; nor have I mentioned the model farm or many additional monuments and follies, not to mention nature walks and the railroad that tunnels beneath the estate. Nevertheless, I will conclude here and admit I ran out of energy both on my visit and in writing this account. Mea culpa. Next visit: Lyme Park

0 Comments

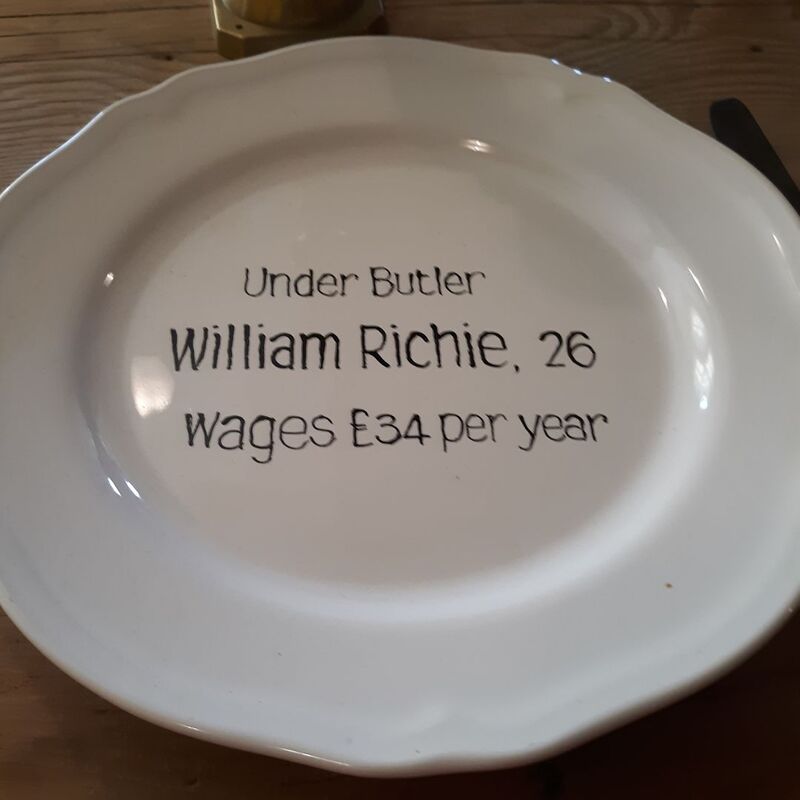

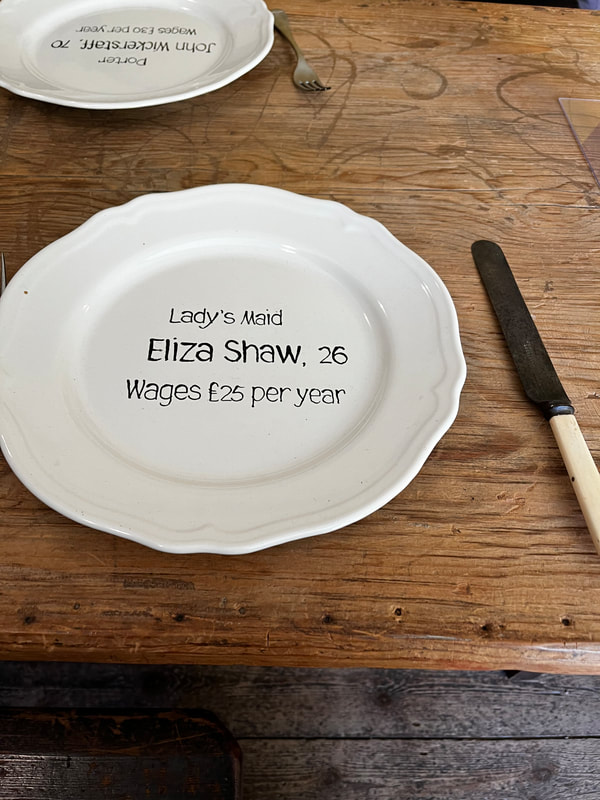

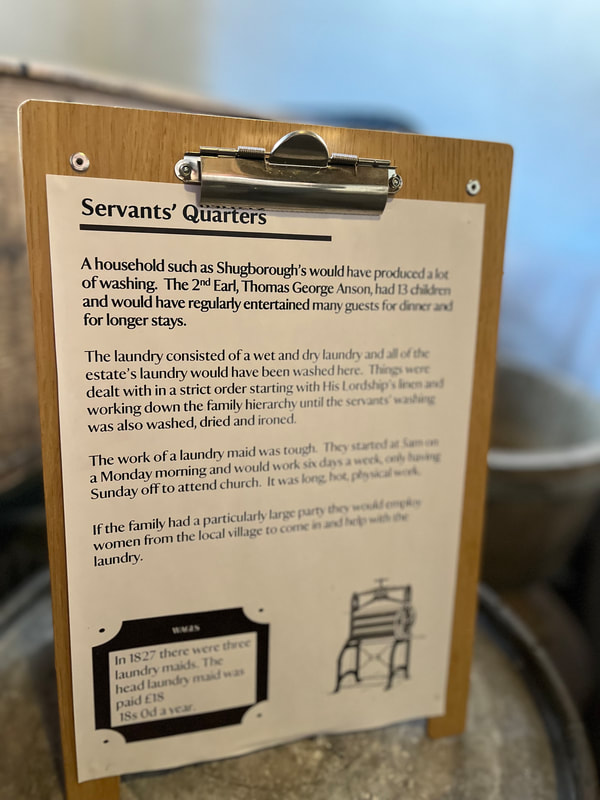

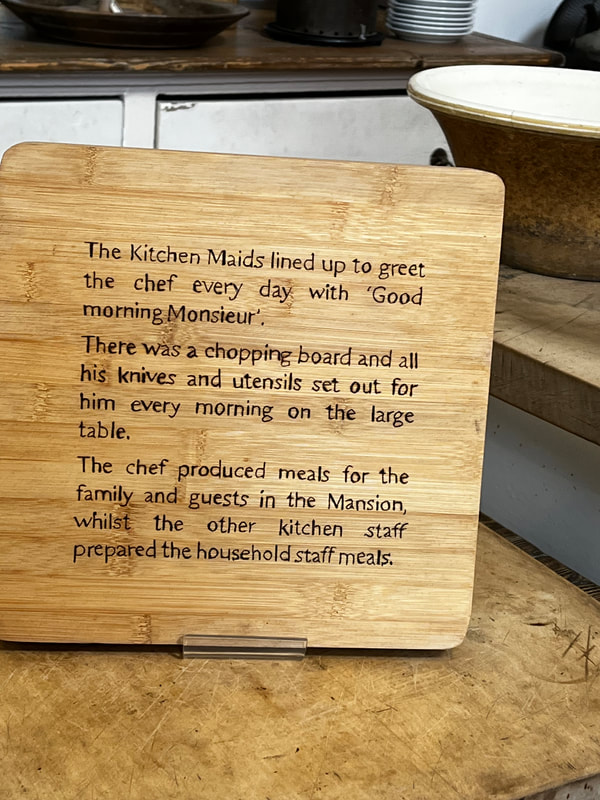

Over the next few weeks, I will present my account of September 2022 visits to six stately homes in England: Shugborough, Harewood, Lyme Park, Castle Howard, Chatsworth, and Marble Hill House, starting below stairs. The Shugborough Servants Quarter is the most comprehensive presentation of how and where the support staff worked of all the Stately Homes I have visited. The National Trust emphasizes more and more how these great estates operated, bringing the visitor downstairs to confront the lives and work of the servants as well as admiring the artistic treasures upstairs. Here in the staff hall, the dining table is set with plates identifying the servants, their ages, and their compensation as it was in 1871. Sample Indoor Servants annual wages: Under Butler William Richie, 26, £34 Housekeeper Sarah Bonham, 48, £52 Lady's Maid Eliza Shaw, 26, £25 Laundrymaid Sarah Walker, 21, £19 Housemaid Jane Thurme, 24, £18 Scullerymaid Sarah Willis, 19, £12 Butler John Crisp 30, £100 Porter John Wickerstaff, 70, £30 About twenty more worked in the gardens, with additional men in the stables, carriage house, etc., as well as home farm employees. Not indicated was the level of housing, clothing, and food provided. Below, scenes in the kitchens. Please click for larger versions. Feeding the family members, guests, and servants required round-the-clock labor. Everything started from 'scratch,' from plucking the feathers from fowl to gathering the eggs for custards. Then the scullerymaid went to work on the pots and pants...what an awful job. Do you polish copper pots? The laundrymaids had equally damp and difficult work. The magnificent contraption below is a stove to keep many irons hot so the maids don't take a break while they reheat one by one. Below, a clock to keep the servants on schedule; baskets of sheets to be laundered using that scrub board; note the rug beater propped up by the window; a prize-winning sirloin of beef on the hoof. Above, objects to decorate the table were stored carefully, and shelves of various jars waited to be filled. On the right, the early sewing machine awaits an ever-present mending basket. Below, the rules for greeting the Chef, assorted bottles, and a napkin press. The outside features were clearly not designed for relaxing if one had a free moment. Servants provided a luxurious life above stairs, but their own existence was entirely different. Next, the upstairs in all its splendor.

My kind of sign!!! Below mosaics from the National Gallery floor...worth a close view. Please click on the smaller photos to see a complete version. Above, two of the "The Modern Virtues" mosaics laid in 1952 by Russian-born artist Boris Anrep (1885-1969), a member of the Bloomsbury group, in the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square. 'Wonder' is, of course, Alice of Wonderland fame, and 'Defiance' is Sir Winston Churchill. Above left, warning signs to tourists at the Shugborough Estate, and another, right, at Harewood where the international drought upset the ferry. Below, one of the many bucolic shots I took as we drove around the rural countryside from stately home to stately home. Below, a unique umbrella stand. Whatever.  |

Victoria Hinshaw, Author

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed